Srebrenica in the public discourse of Serbia

The Srebrenica Genocide - Facts

On 16 May 1992, the Assembly of the Republic of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) adopted six strategic objectives for the Serbian people in BiH. As one of those objectives, they stipulated “the eradication of the Drina as a border between the Serbian states.” On 19 November of the same year, the Commander of the Main Staff of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), Ratko Mladić, issued Directive 04, ordering the VRS Drina Corps to: “[…] exhaust the enemy, inflict the heaviest possible losses on them and force them to leave the Birač, Žepa and Goražde areas with the Muslim population”. As a result of the VRS operations in eastern Bosnia during 1992 and early 1993, Muslims from the Drina River Valley took refuge in the enclaves of Srebrenica, Žepa and Goražde. Srebrenica, the shelter for about 40,000 refugees, was declared a “protected zone” by the UN Security Council on 16 April 1993.

On 8 March 1995, the President of Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, signed Directive 07, ordering the creation of “an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the local inhabitants of Srebrenica and Žepa.” On 2 July 1995, the Commander of the VRS Drina Corps, Milenko Živanović, issued an order for Operation Krivaja ’95, and in accordance with this order, on 6 July Serb forces launched an attack on the “protected zone” of Srebrenica, under Mladić’s command.

There was no resistance from the BiH Army or international forces in Srebrenica, so the enclave’s population – mostly women, children and elderly men – headed to the Dutch UNPROFOR battalion base in the nearby village of Potočari, where they sought protection. About 15,000 men, civilians and soldiers lined up with the intention of making their way through the forests to the territory under the control of the BiH Army. Ratko Mladić entered the deserted city with his army on 11 July and announced “revenge on the Turks” in the presence of the cameras.

On 12 July, the deportation of refugees from the UN base in Potočari began, by buses organized by the VRS. However, only women, children and the elderly were allowed to enter the buses, and military-aged men were taken to detention facilities. The line of people making its way through the forest was exposed to continuous VRS fire, while Serb soldiers organised ambushes and called on people from the line to surrender. Those who were captured or surrendered were taken to temporary detention facilities in the municipalities of Srebrenica, Bratunac and Zvornik. On 13 July, mass executions of detained Muslims began.

From 11 July to around 16 July 1995, Serb forces shot and killed around 8,000 Bosnian Muslims, men and boys at several locations in Srebrenica, Bratunac and Zvornik. About 25,000 women, children and the elderly were displaced from this part of eastern Bosnia.

The Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) began a criminal investigation into the Srebrenica crimes in July 1995. A dozen male survivors of the mass executions testified before the ICTY, as did numerous other witnesses to the crime. The first exhumations of mass graves began in July 1996, and the evidence has been discovered that in the autumn of 1995, in a secret operation to cover up the traces of the crime, the bodies of Srebrenica victims were being moved to secondary graves. Forensic reports, intercepted conversations and many other documents, witnessing to the planning and scale of the crime, have been discussed in the evidence hearings of the Srebrenica trials.

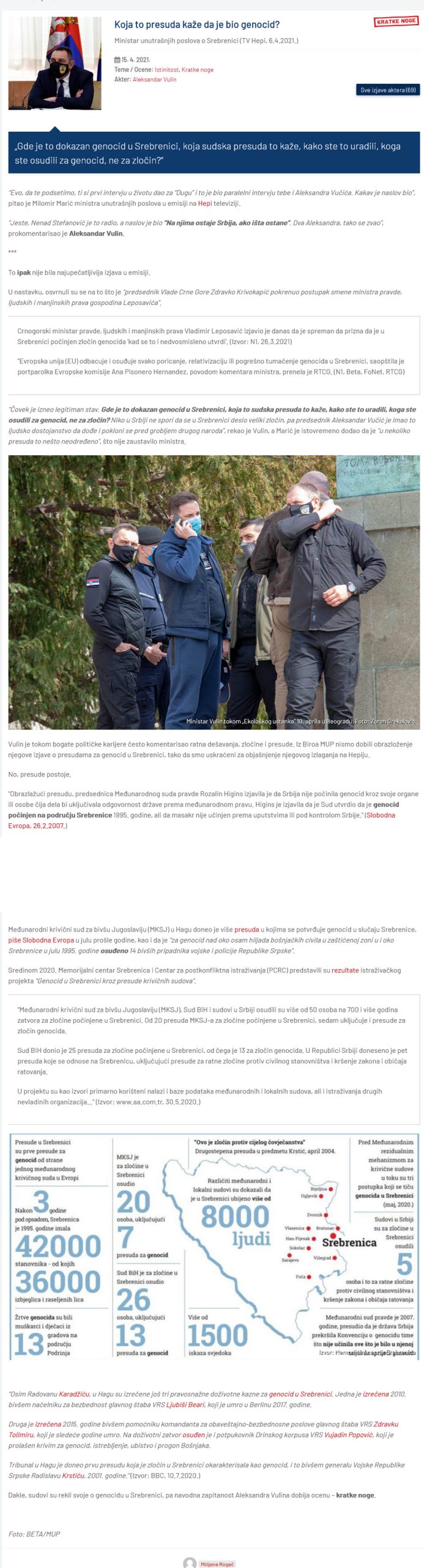

Sixteen people have been convicted of crimes in Srebrenica before the ICTY, seven of them for genocide. The first final verdict for the Srebrenica genocide was handed down in the Krstić Case on 19 April 2004. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) acted on a lawsuit filed by BiH against Serbia and Montenegro for genocide, and ruled, on 26 February 2007, that Serbia had not, through its institutions, committed genocide in Srebrenica, but was responsible for violation of the Genocide Convention, because it had not done everything in its power to prevent the genocide, and afterwards had not done enough to prosecute those responsible for this crime. Before the Court of BiH, 25 people have been convicted for crimes in Srebrenica, 13 of them for genocide. Before the High Court in Belgrade, no one has been tried for genocide. Five people were convicted of killing six civilians in Trnovo, but in the verdict issued in April 2007, the Court left out the fact that those six civilians were brought from Srebrenica.

Three courts – two international and one domestic – have found, in a number of cases presided over by a large number of judges, that genocide was committed in Srebrenica in July 1995.

Media coverage in July 1995

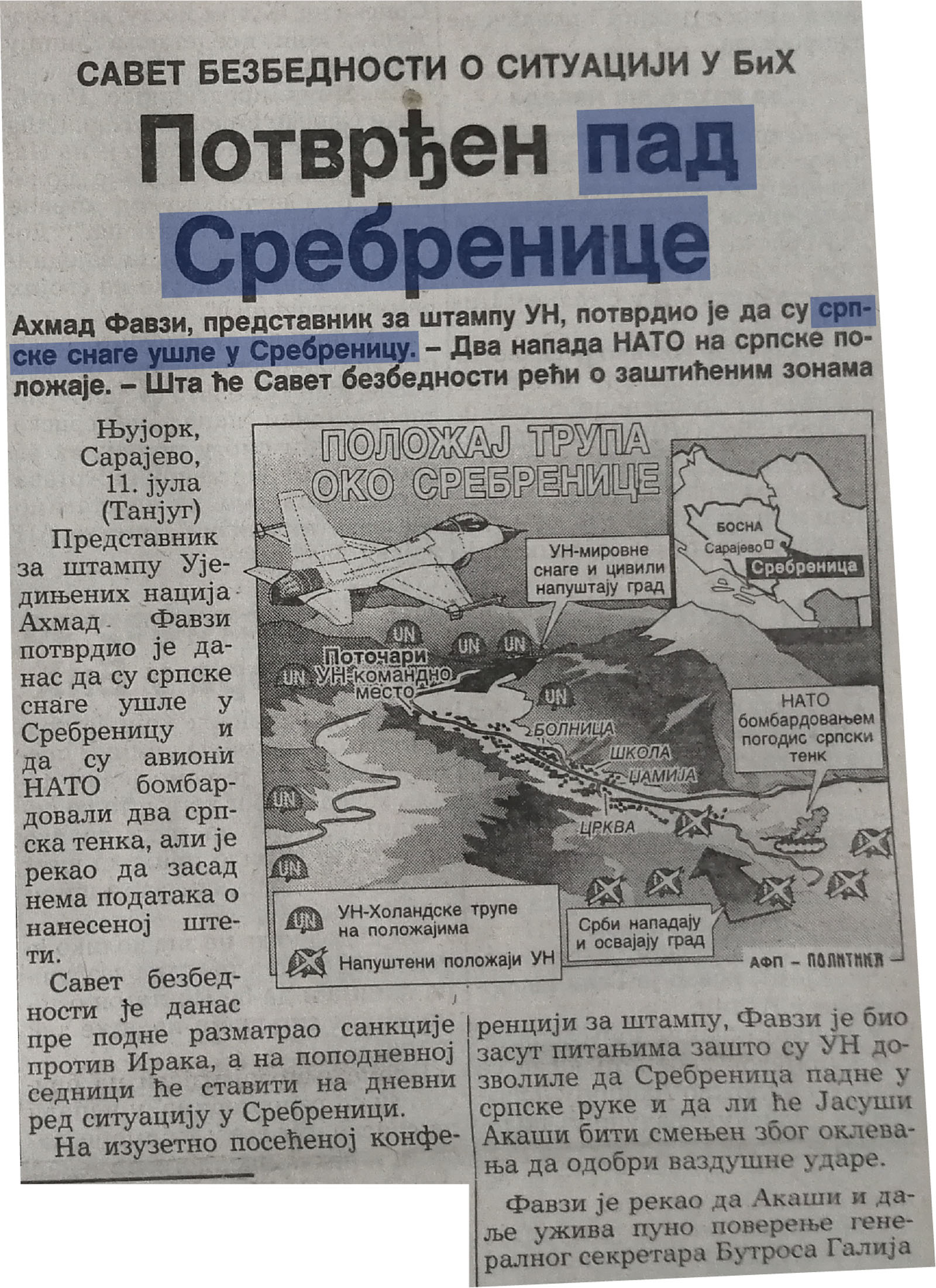

At the time of the attack by Serb forces on the Srebrenica enclave in July 1995, all media in Serbia reported on the war in BiH, including this event. In Večernje novosti, for example, news about Srebrenica was being featured on the front page for seven consecutive days, from 12 July to 18 July 1995.

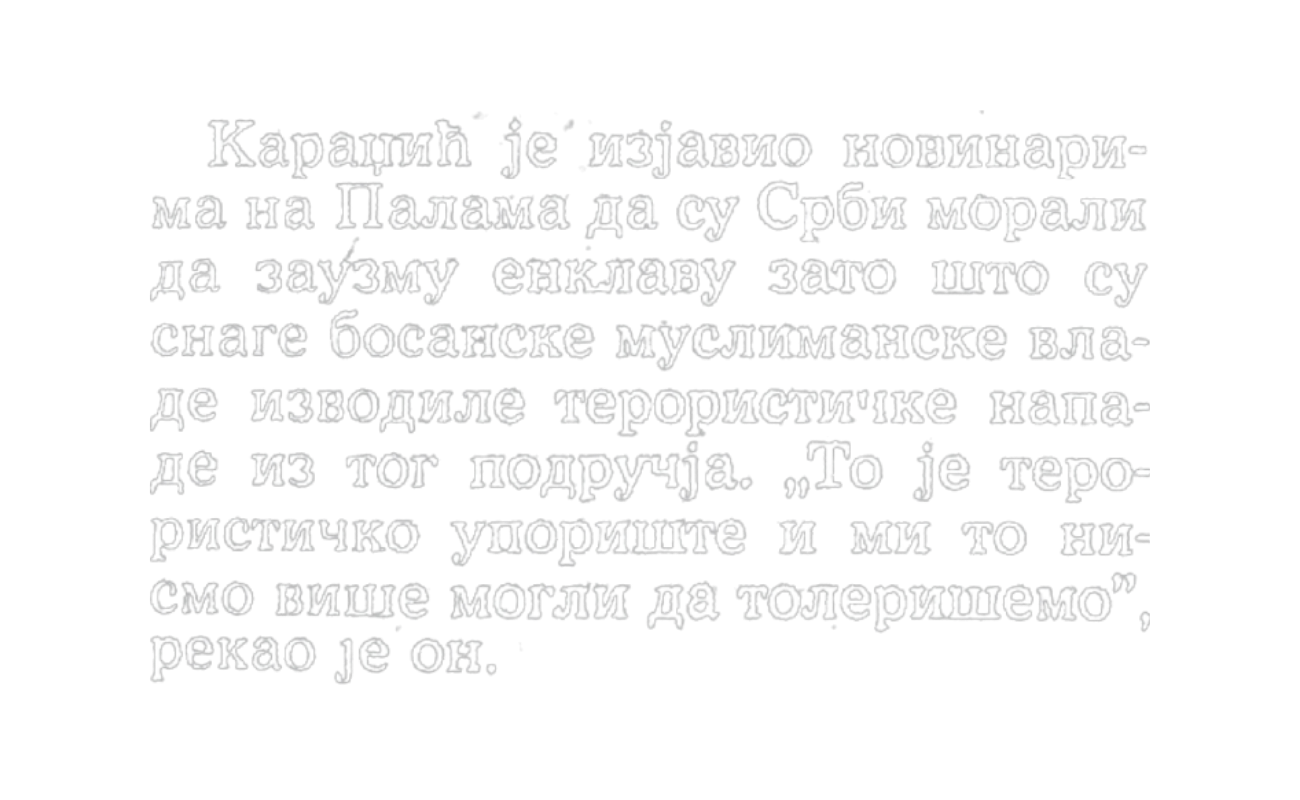

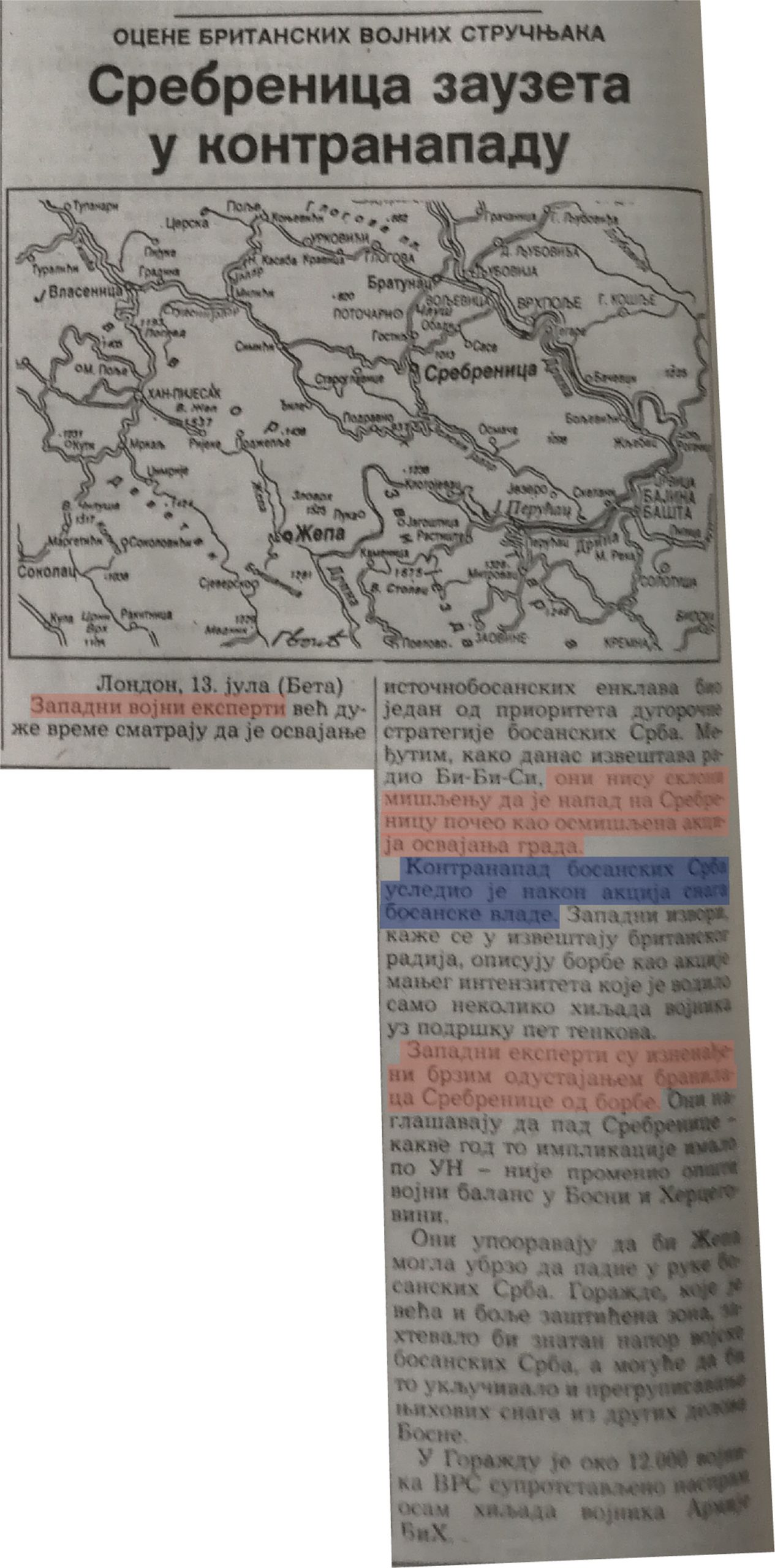

The entry of the VRS into the “UN protected zone” in the Serbian press was generally called the “entry of Serb forces into Srebrenica” and the “fall of Srebrenica”, but also the “liberation” of Srebrenica and the “successful counterattack” of Serb forces. In nationalist newspapers whose editorial policy was close to the then regime, such as Večernje novosti and Politika ekspres, the dominant narrative portrayed Bosnian Muslim forces as Muslim “terrorists”, “extremists” and “fundamentalists”, and the VRS actions in Srebrenica as combatting against Muslim terrorism and self-defence. Politika newspaper also quoted statements of Bosnian Serb leaders about alleged Bosnian Muslim terrorism:

At the time of the attack on Srebrenica and in the days that followed, it was important to the pro-regime media to convey messages that civilians and members of the international forces in the Srebrenica area were allegedly safe, that they were not the target of attacks, and that the VRS treated them humanely and in accordance with the Geneva Conventions.

Some newspapers, such as Naša Borba, but also Dnevnik, and even Politika in a July issue, quoted statements calling the deportation of refugees from Srebrenica and the way the VRS treated them “ethnic cleansing”, “ethnic terror” and “violation of human rights of the civilian population”.

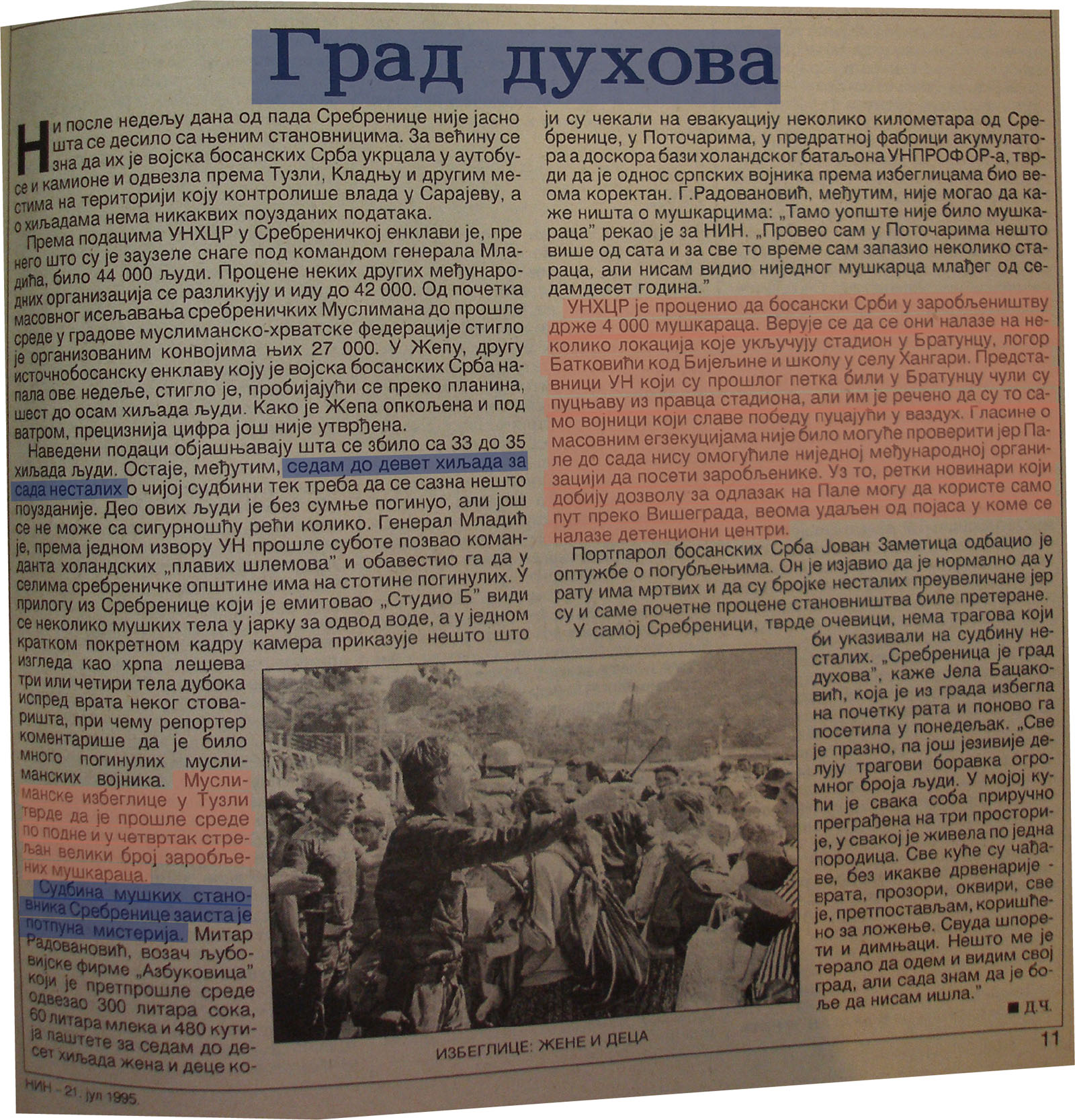

On 20 July 1995, the weekly NIN published the article “Ghost Town”, where it was pointed out that it was unclear what had happened to “the seven to nine thousand people missing so far.” “The fate of the male inhabitants of Srebrenica is truly a complete mystery,” the article reads.

It is clear from this text that manipulations with the number of victims, as well as a denial that the crime had happened, began as early as July 1995.

According to Stanley Cohen,[1] there are three basic states of denial: literal denial, which means denying that something happened at all, that is, denying the facts themselves; interpretative denial, meaning a rejection of a certain interpretation of an event – for example, of the legal description of an act, but also the rejection of responsibility for an act; and implicative denial, which encompasses a whole range of narrative strategies, from invoking the principle of necessity, or shifting blame to the victim, to attempts to discredit those who make accusations of atrocities. In the public discourse of Serbia regarding Srebrenica, from 1995 until today, the most common form of denial is interpretative denial, and then implicative denial. The denial that anything happened in Srebrenica in July 1995 has been difficult to sustain; but a denial of the facts, such as the number of people killed or their civilian status, has continued being maintained.

1996-2000.

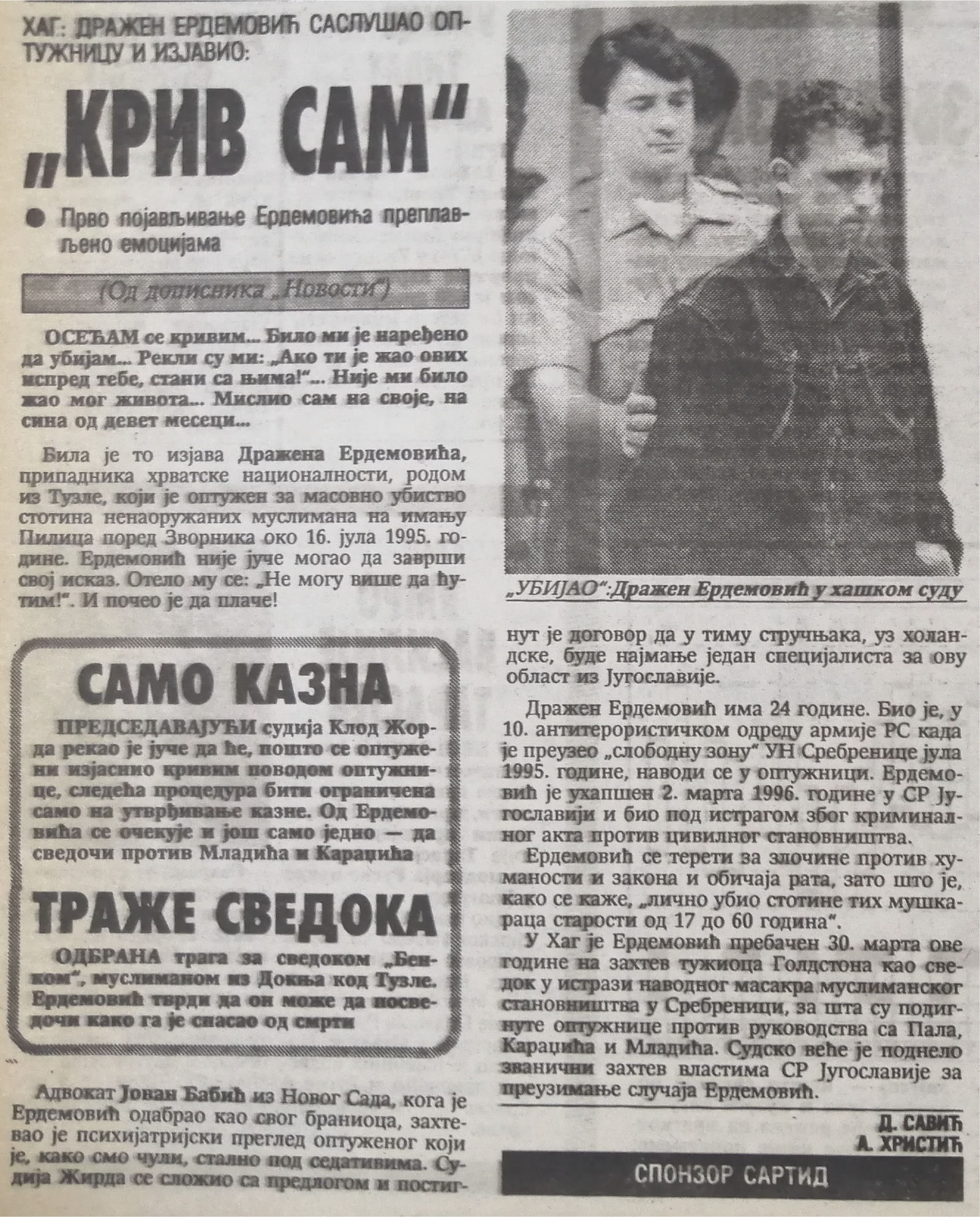

Up till the end of Slobodan Milošević’s rule, conflicts over the interpretation of what had happened in Srebrenica in July 1995 were still not widely present among the public, but silence was dominant. In this period, Srebrenica was being mentioned in the media only sporadically and in connection with other events that were the main news – mostly in the summer of 1996, in connection with the ICTY indictments against Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić and the issuance of international arrest warrants for them, but also in connection with the admission of guilt of Dražen Erdemović, a member of the 10th Sabotage Detachment of the VRS Main Staff, who took part in the execution of Srebrenica victims.

Večernje novosti, for example, sought to portray the indictments and warrants against Karadžić and Mladić, as well as foreign media coverage, as interference by the international community in internal affairs (specifically, in the September 1996 elections in BiH), international pressure and threat (of imposing sanctions on FR Yugoslavia and Republika Srpska), “a grandiose campaign against RS, FRY […]”, “an hysterical anti-Serbian campaign”, “the circus act in The Hague”, etc. In almost all the articles on indictments and arrest warrants published by Večernje novosti was to be found a common insistence that the indictments had been directed against the entire Serbian people.

On the fifth anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, in July 2000, the opposition media, such as the daily Danas, began reporting on the commemorations of Srebrenica victims and demands for the prosecution of indictees – without questioning the crime itself or its scale.

2001-2003.

When the regime of Slobodan Milošević was overthrown on 5 October 2000, an ideologically heterogeneous coalition – the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) – whose only common denominator was resistance to Milošević, came to power.[2] A new Serbian government headed by Zoran Đinđić was formed and some progress was made in dealing with the past: mass graves with the bodies of killed Albanians were discovered and Slobodan Milošević was extradited to the ICTY. However, there was no political will to raise the issue of state responsibility for war crimes in Serbian institutions.[3] Cooperation with the ICTY became a point of division within the DOS, but also in society as a whole. The nationalist section of the intellectual elite openly came to the defence of those indicted for war crimes and significantly contributed to the spread of narratives about the ICTY as an anti-Serbian court.[4] Therefore, in the first years after the fall of Milošević, the opportunity to move away from his nationalist policy was missed.

In this period, conflicts over the interpretation of what happened in Srebrenica were still in their beginning

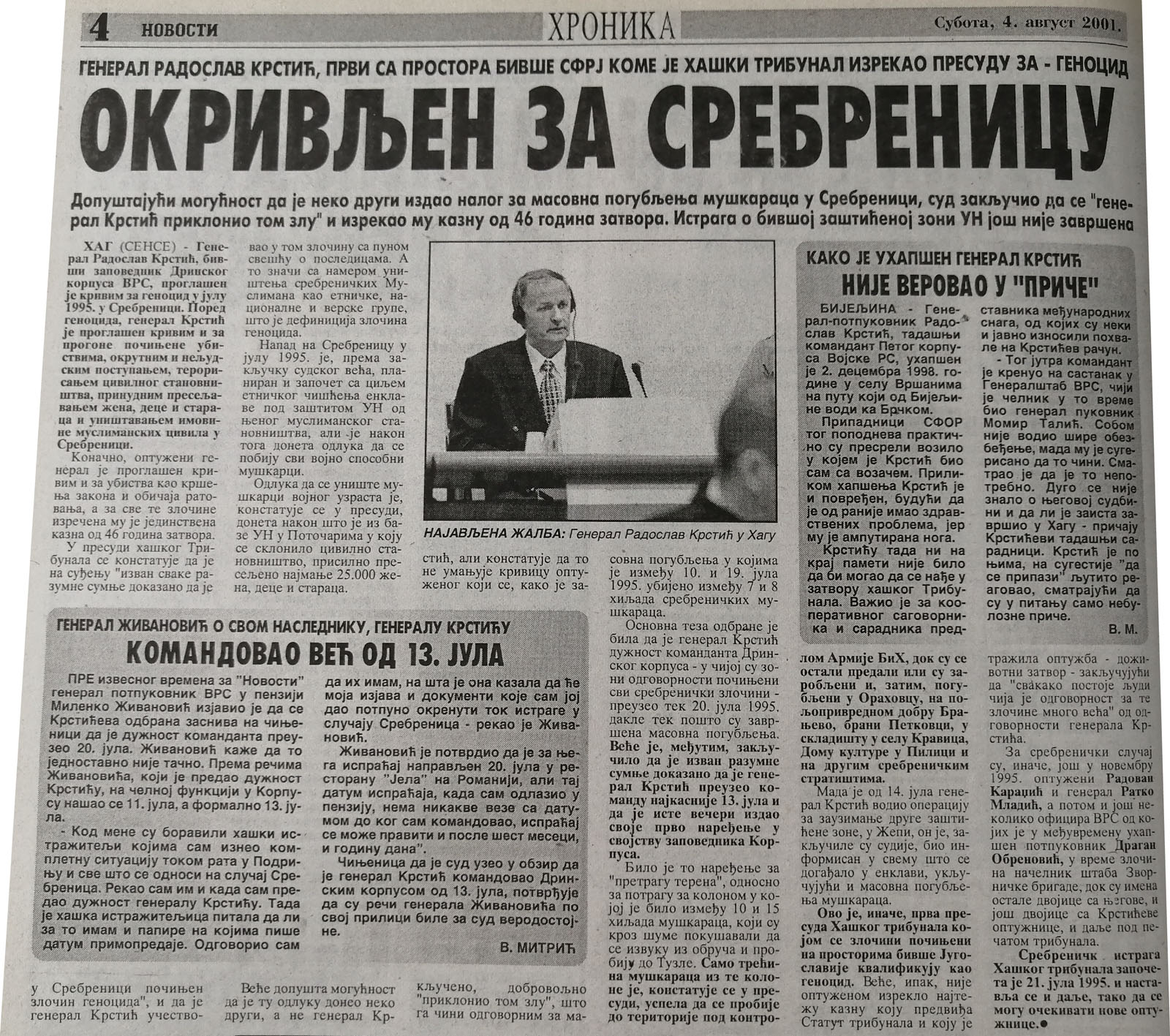

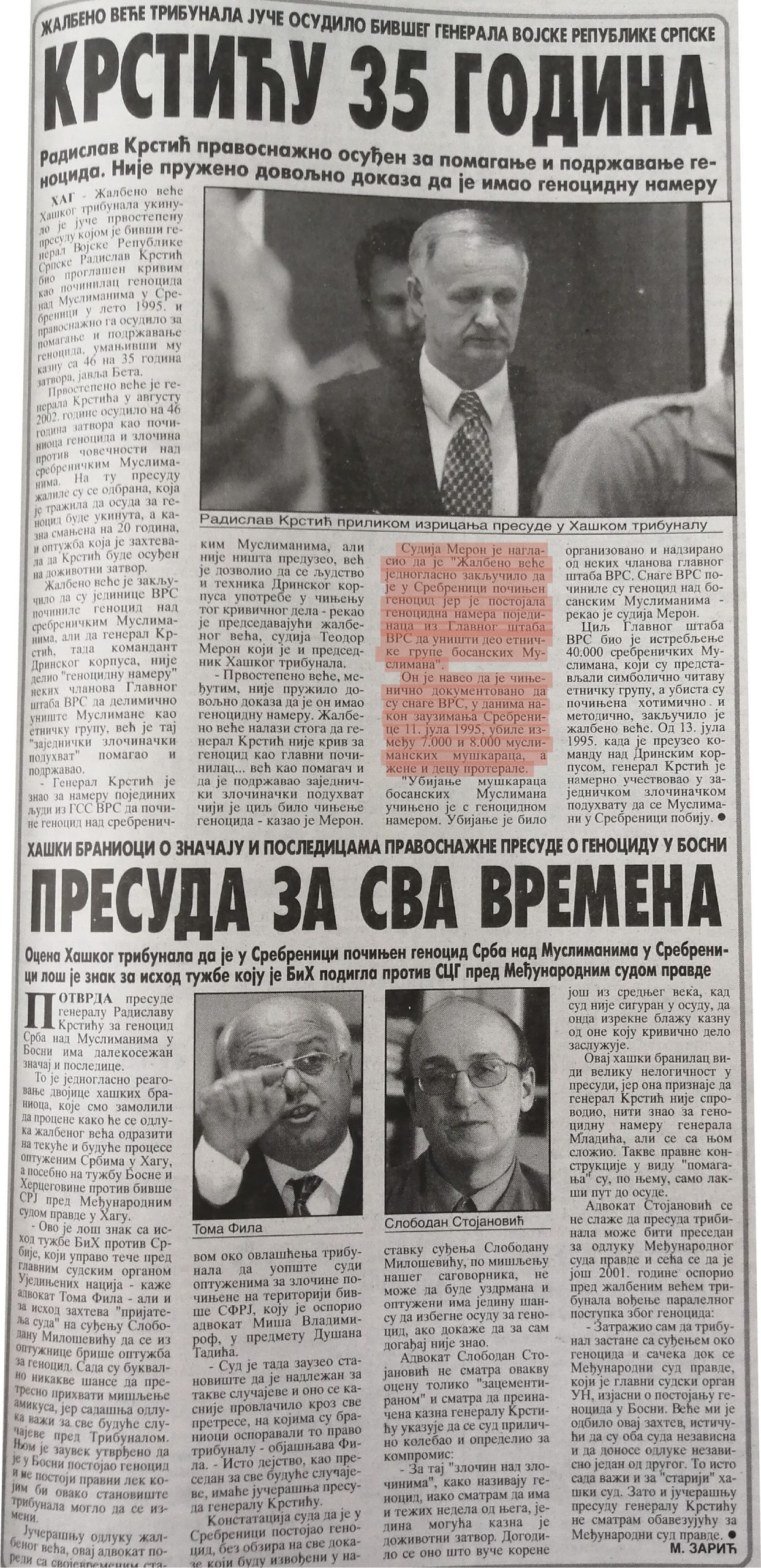

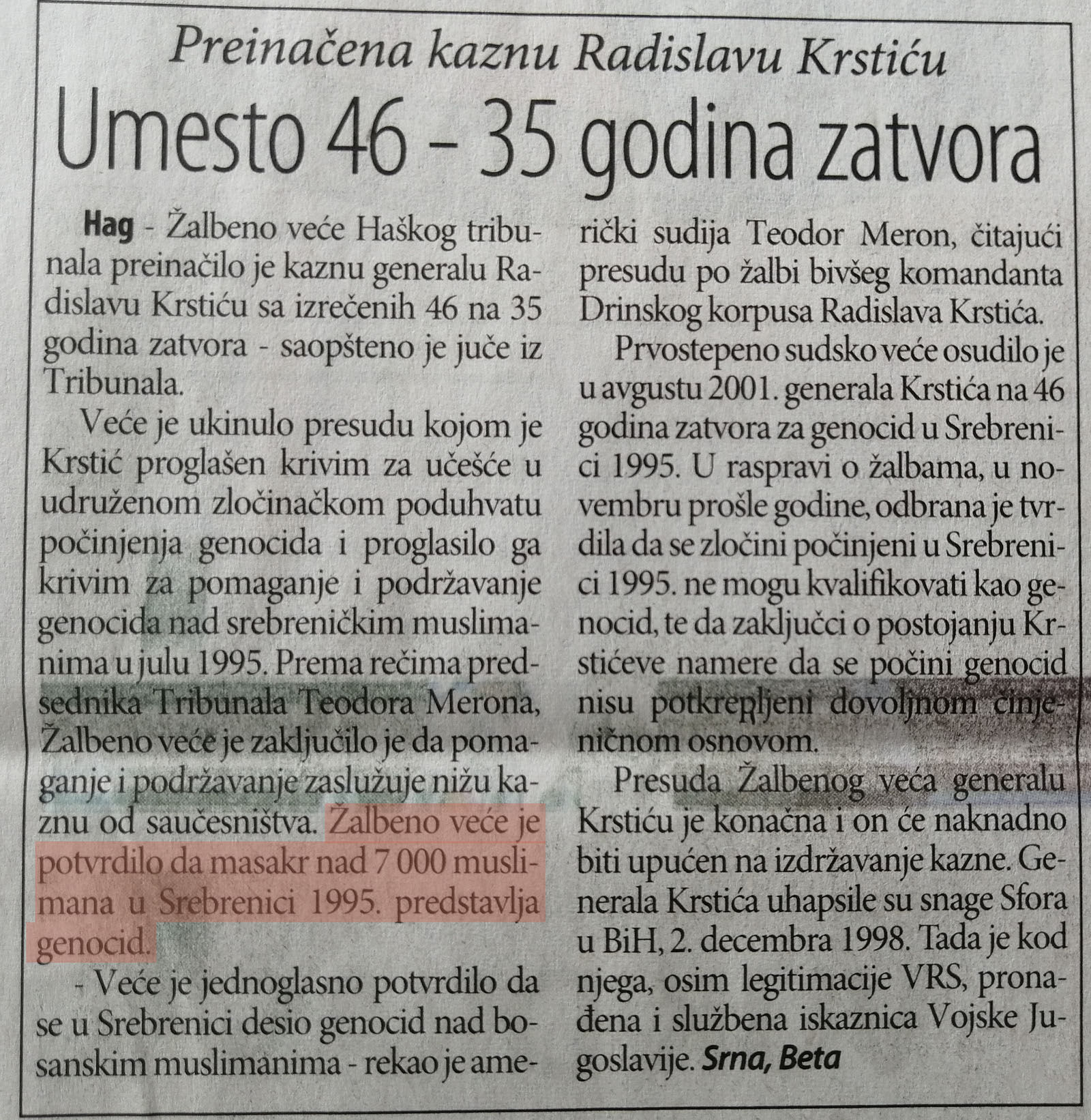

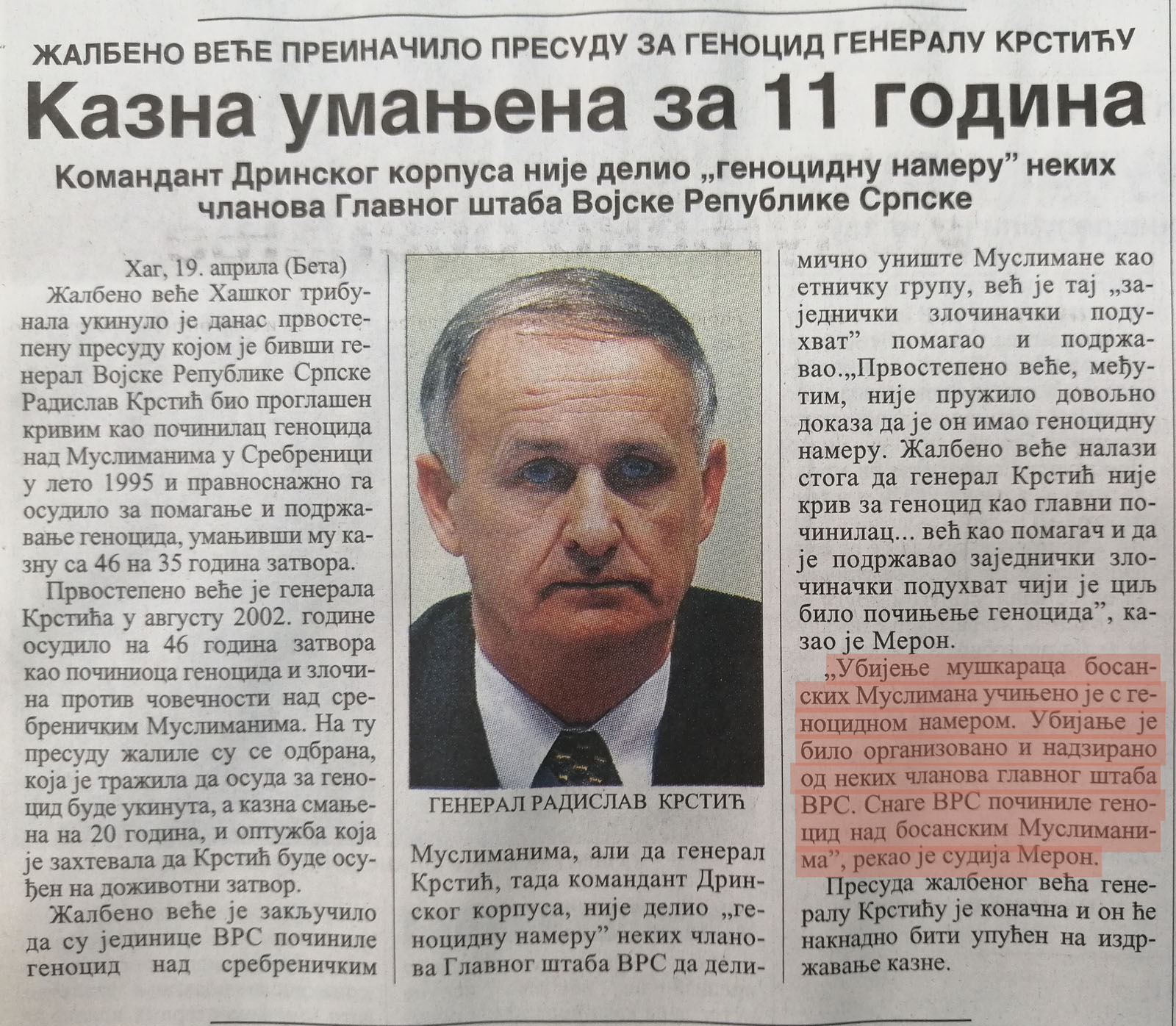

On 2 August 2001, the ICTY handed down a first-instance verdict against VRS General Radislav Krstić, convicting him, among other things, of genocide in Srebrenica. This was the first verdict for genocide committed in Europe since World War II. The reporting of the highest-circulation domestic dailies on the Krstić verdict differed only subtly: for example, while Danas mentioned genocide in its headlines, Politika and Večernje novosti did not. Serbian state officials did not publicly comment on the verdict.

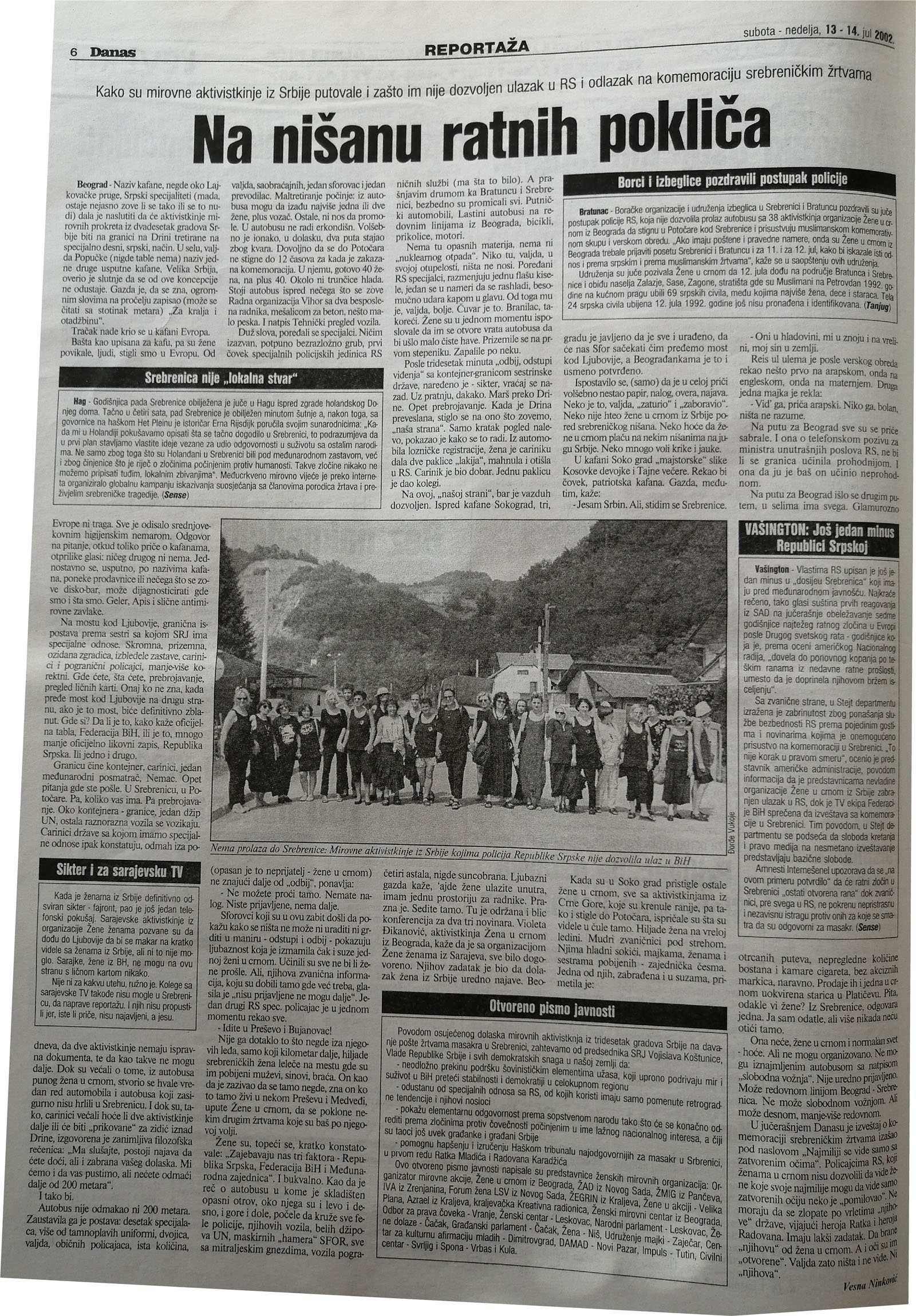

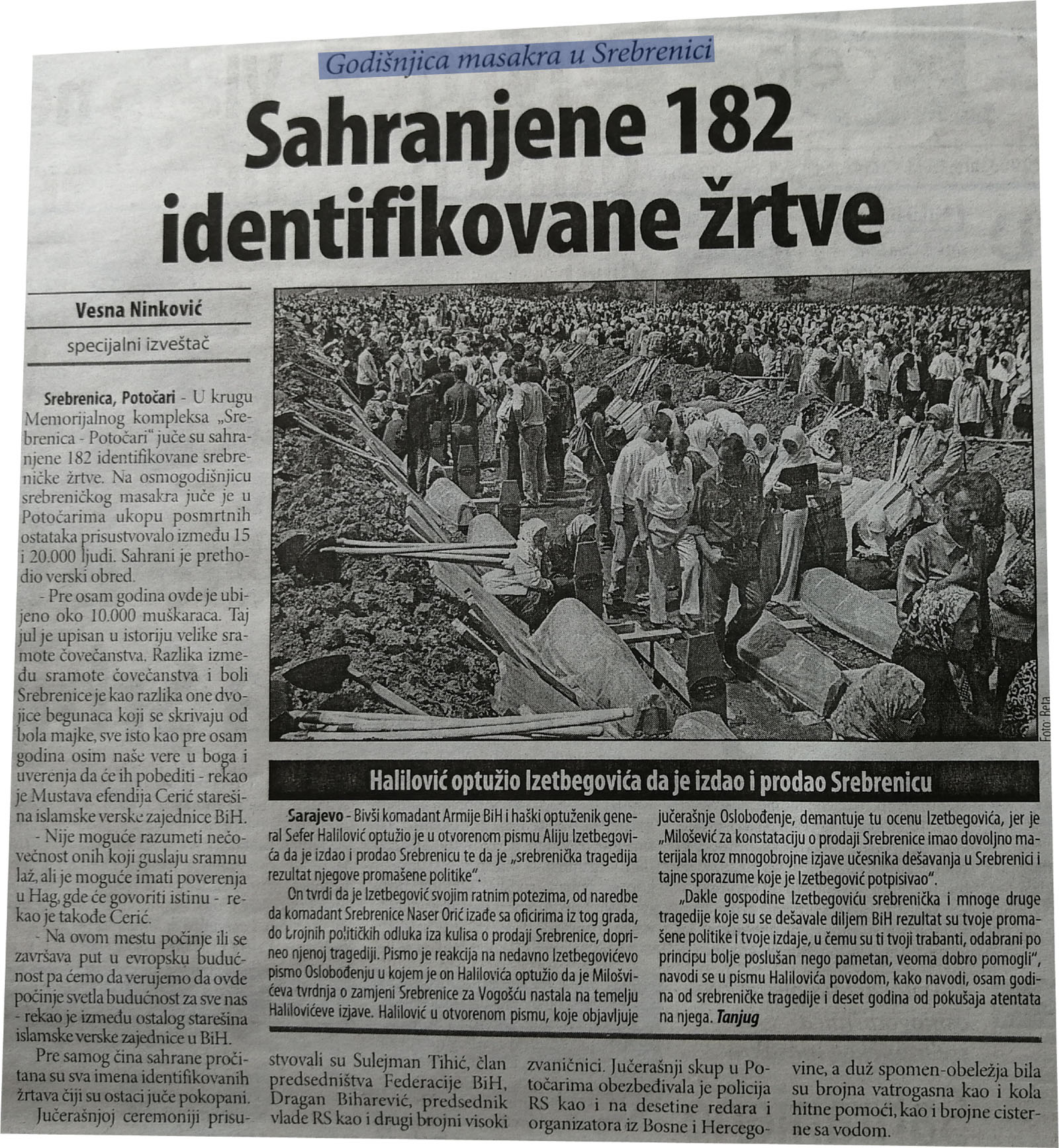

Since 2000, Danas has been regularly reporting on commemorations in Potočari, where the cornerstone of the Srebrenica Memorial Centre was laid in 2001, but also on the Women in Black commemorations in Belgrade, and other commemorations of Srebrenica victims around the world. Despite the first-instance verdict against Krstić, the crime in Srebrenica was described in the Serbian media mainly as the “massacre in Srebrenica” – in Politika, as a “tragedy” and “suffering of Bosniaks”.

In its reporting on the trial of Slobodan Milošević before the ICTY, Politika sought to point out that Ratko Mladić had not been in any way subordinate to Belgrade.

2004-2008.

The assassination of Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić on 12 March 2003, and the short-lived government of Zoran Živković, were followed by the four years of the first and second governments of Vojislav Koštunica, who continued to marginalise the issue of dealing with the war legacy of the 1990s, and provided institutional support to ICTY war crimes indictees (for example, through the Law on the rights of The Hague indictees and their families)[5] Boris Tadić, the leader of the Democratic Party (DS), was the President of Serbia at the time.

In this period, there were four events important for Serbia’s attitude towards what had happened in Srebrenica in July 1995: the first final verdict for the Srebrenica genocide (April 2004), the publication of footage of the execution of Srebrenica detainees (June 2005), the visit of the President of Serbia, Boris Tadić, to the commemoration in Potočari (July 2005), and the ICJ judgment on the lawsuit of BiH against Serbia and Montenegro (February 2007).

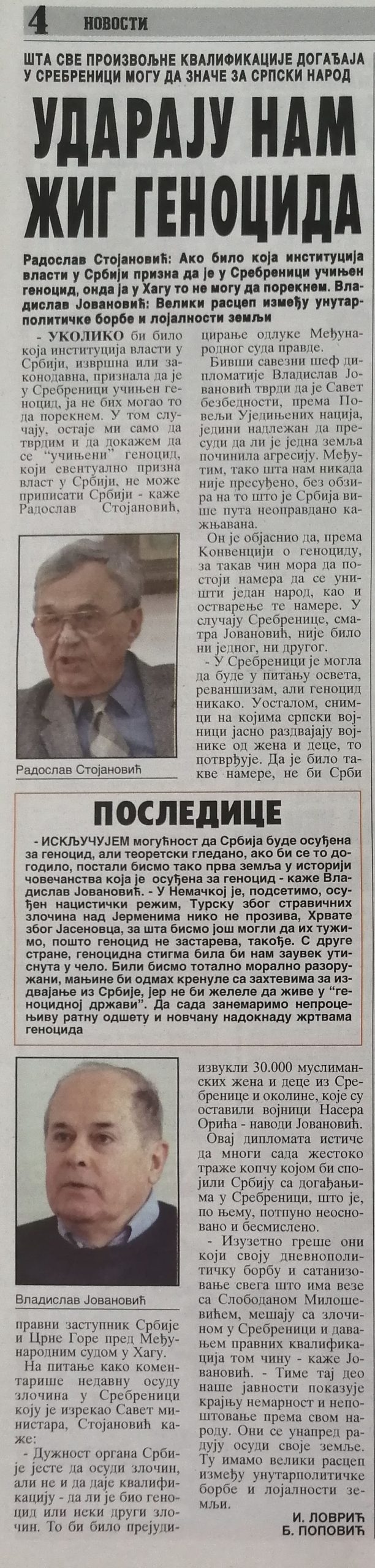

In April 2004, the ICTY Appeals Chamber handed down a verdict in the Krstić Case, finding Radislav Krstić guilty, among other things, of aiding and abetting genocide. The first final verdict qualifying the Srebrenica crime as genocide did not provoke public reactions from state officials in Serbia. The next day, Večernje novosti published an article about the alleged prevention of Republika Srpska’s Srebrenica Commission from reaching the “complete truth” about Srebrenica, with a subtitle that read: “They are not victims of genocide.” Following the first final verdict for genocide, denial of the legal description began, as a type of interpretative denial.

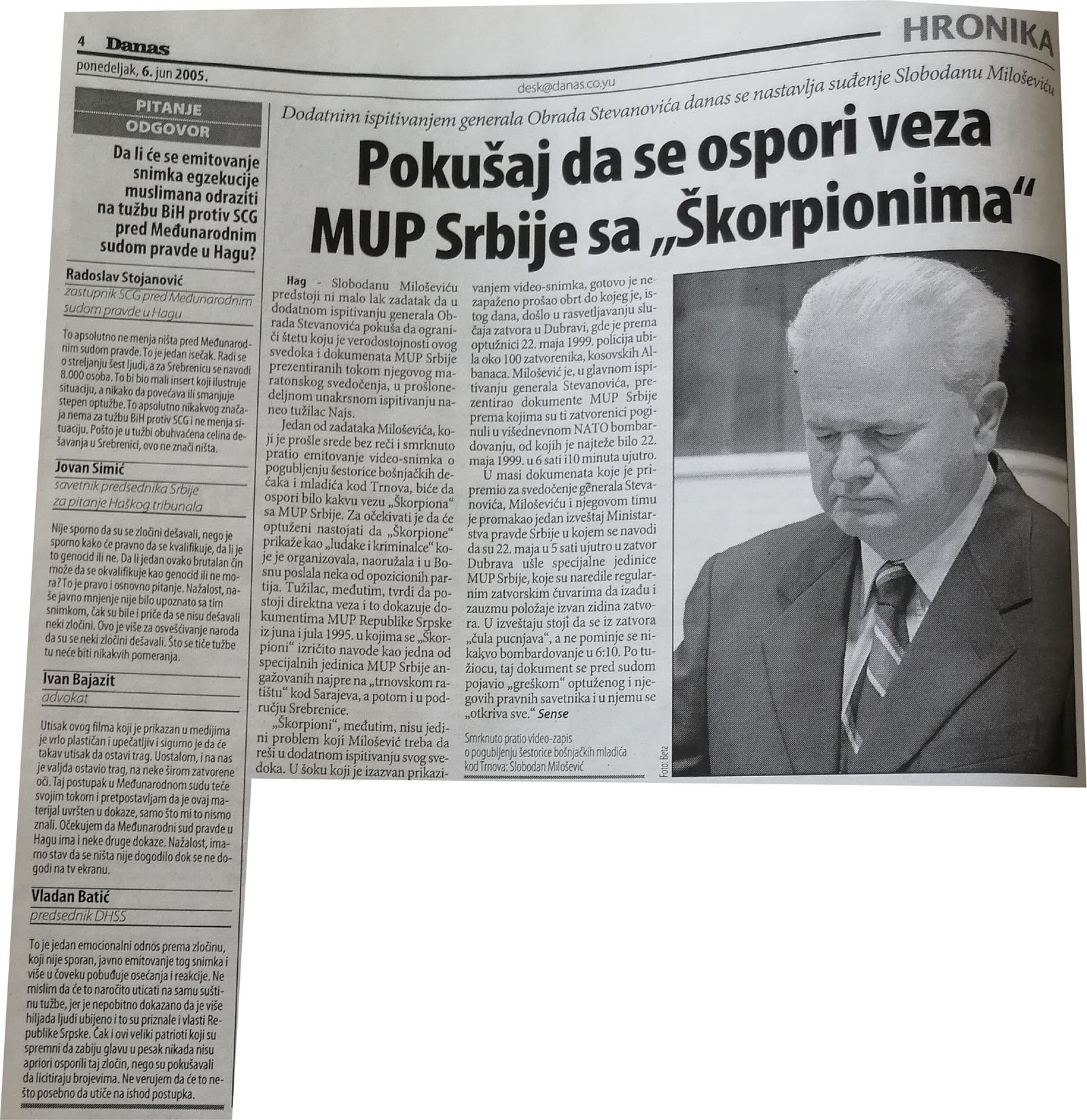

On 1 June 2005, at the trial of Slobodan Milošević before the ICTY, a video made in July 1995 in Godinjske Bare, near Trnovo (BiH), was played, showing members of the “Scorpions” shooting six captured civilians from Srebrenica, two of whom were minors. Thanks to the Humanitarian Law Centre (HLC), the video was shown on television in Serbia. This forced the public to face the long-suppressed truth about the war in BiH: after the shocking scenes from this authentic footage, it was no longer possible to deny brutal killings of civilians and prisoners committed by Serb forces (literal denial), but more sophisticated forms of denial and relativisation intensified.

One direction of denial was the denial of the connection between the “Scorpions” and the state of Serbia, by insisting on the “individual” crime and the exclusive responsibility of direct perpetrators (denial of the responsibility of institutions, as a form of interpretative denial). Advocates of this narrative generally implied that connecting “Scorpions” with the institutions of the Republic of Serbia would imply the guilt of the entire Serbian people for crimes committed by individuals, and that that must be prevented. The other direction was the relativisation of the crimes in Trnovo by pointing out that all parties in the war had committed crimes, and also by pointing out crimes against Serbs, announcing footages of crimes against Serbs, and even, in some cases, justifying the crimes committed by members of Serb forces by previous crimes committed against Serbs (shifting the blame to the victim, as a form of implicative denial).

The publication of the video of the execution of the six Srebrenica residents led to a debate in the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia on a declaration condemning all war crimes. However, the members failed to agree on the text of the declaration, because the DS believed that Srebrenica should be mentioned in the title, and this was strongly opposed by the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS), the Serbian Radical Party (SRS) and the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS).

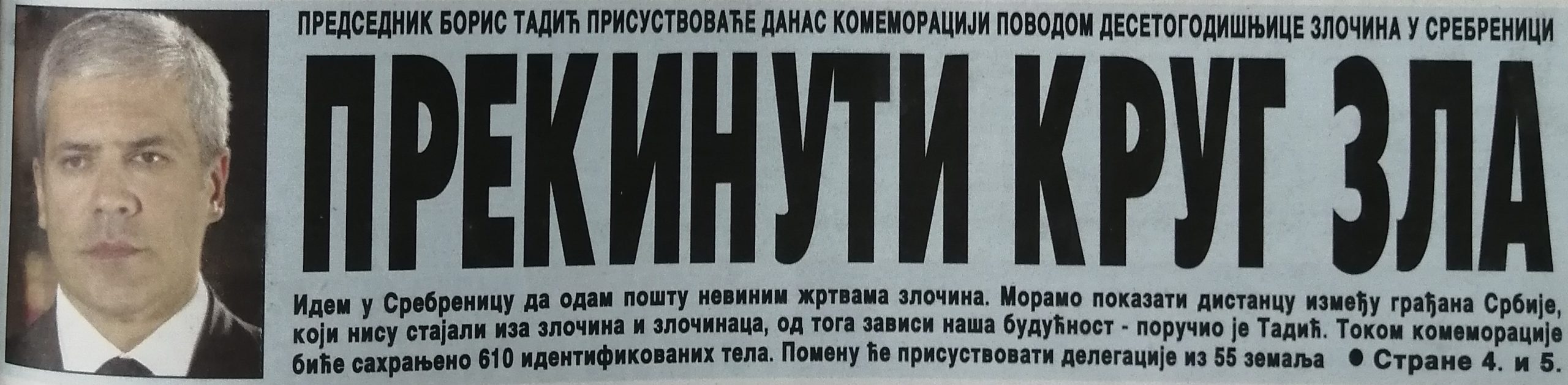

Immediately after the broadcast of the “Scorpions” video, the then President of Serbia, Boris Tadić, announced that he would attend the commemoration in Potočari in July, pointing out that “crime is never collective” and that “culprits must always be found and convicted.” Tadić’s visit to Potočari went peacefully and without incident, and this was the first time that a high Serbian official had attended a commemoration of Srebrenica victims.

Tadić did not accept the legal description of the ICTY, so he did not talk about the Srebrenica genocide, but about the “crime”. Meanwhile, in the days immediately before and after the tenth anniversary, Večernje novosti published a number of articles denying the genocide, and also denying the number of Srebrenica victims.

On 26 February 2007, the ICJ, the highest judicial body of the United Nations, delivered a judgment on the lawsuit of BiH against Serbia and Montenegro for genocide. The judgment found that Bosnian Serb forces in Srebrenica had committed genocide against Bosnian Muslims in July 1995. Furthermore, it was found that the FRY had a significant influence on the Bosnian Serbs and that there were strong political, military and financial ties between the FRY on the one hand, and the Republika Srpska and the VRS on the other. However, the court held that the subjects who committed genocide did not have the status of organs of the FRY, and that the genocide was not committed by the order or under the control of the FRY; so the judgment concluded that the FRY did not commit genocide in Srebrenica. However, the ICJ ruled that the FRY had not done everything it could to prevent the genocide in Srebrenica, and that it had not done enough to prosecute the indictees, and was therefore responsible for violating the Genocide Convention.

The fact that Serbia had been acquitted of one part of the charges (of committing genocide in BiH) by the ICJ judgment, created space for media manipulation of the facts about this judgment. Officials in Serbia, as well as the media, welcomed the judgment, emphasising only its acquitting part. Triumphant headlines appeared on the front pages: “Serbia is not guilty of genocide”, “Serbia acquitted of genocide”, “Serbia is not guilty”, etc. These headlines did not mention the condemnatory part of the judgment, thus creating a false idea among the readers, although the condemnatory part was usually mentioned in the continuation of the texts. The fact that the ICJ judgment had confirmed the legal description of the Srebrenica crime, i.e., that it had established that the crime was genocide, was almost completely pushed aside, and in some cases, genocide was being directly denied (e.g., in the statements of Republika Srpska officials broadcast by Serbian media, on the front page of Večernje novosti, and elsewhere).

The then Minister of Foreign Affairs of Serbia, Vuk Drašković, pointed out that this judgment “removed the stigma of genocide” from the Serbian people – although the Serbian people have never been accused, which is legally impossible anyway – and thus contributed to the narrative that establishing the responsibility of the state meant, at the same time, the collective guilt of the whole nation. The DS Vice-President, Dragan Šutanovac, made a similar claim, saying that “it is a good thing for everyone living in Serbia that our country hasn’t been marked as genocidal”, because otherwise “all of us would be stigmatised”.

Since this period, denial of the legal description and denial of responsibility (as forms of interpretative denial) have become dominant; but some other forms of denial also persist (e.g., invoking the principle of necessity and blaming victims).

2008-2011.

The Republic of Serbia formed a new government on 7 July 2008 and Mirko Cvetković from the DS party was appointed Prime Minister. However, in order to form the government, the DS had to form a coalition with the SPS party. The new coalition partners signed a Declaration on Political Reconciliation, which did not address war crimes and transitional justice. Thus, Slobodan Milošević’s party had returned to power less than a decade after the end of the wars, without any deviation from the war policy of the 1990s. Boris Tadić was still the President of Serbia.

Only two weeks after forming the new government, Radovan Karadžić, the former president of Republika Srpska and one of the two most wanted Hague indictees at the time, was arrested and charged, among other things, of genocide in Srebrenica. Karadžić was arrested in Belgrade, where he had lived under a false identity for years. Shortly after his arrest, he was transferred to The Hague, and his trial before the ICTY began the following year.

Reactions to Radovan Karadžić’s arrest in Serbia were mixed, even within the ruling coalition. The President of Serbia and the Prime Minister, both from the DS, welcomed this arrest, primarily as a proof of Serbia’s commitment to international and domestic law, and to fulfilling its international obligations. However, their SPS coalition partner issued a statement in which it is said that this party “opposes the extradition of Serbian citizens [to the ICTY], despite the fact that co-operation with that court is an international obligation of Serbia […]”. The statement also points out that the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Serbia, which had been put in the hands of SPS leader Ivica Dačić as its new head a few weeks earlier, had “nothing to do with locating and arresting Karadžić.”

Most of the political actors at the time shared a negative attitude towards Karadžić’s arrest. DSS leader Vojislav Koštunica linked the event to pressure from the international community for Serbia to recognise Kosovo’s independence, and the then SRS Secretary-General Aleksandar Vučić said the news of the arrest had been “horrible news” and that Serbia was “on the verge of extinction”:

The European Parliament adopted a resolution in 2009 declaring 11 July a day of remembrance for the Srebrenica genocide, so 100 Serbian NGOs asked President Tadić to acknowledge this date in the same way in Serbia. However, that proposal was not adopted, and the state institutions of Serbia continued to deny the legal qualification of the Srebrenica crime, as well as to persist in its relativisation.

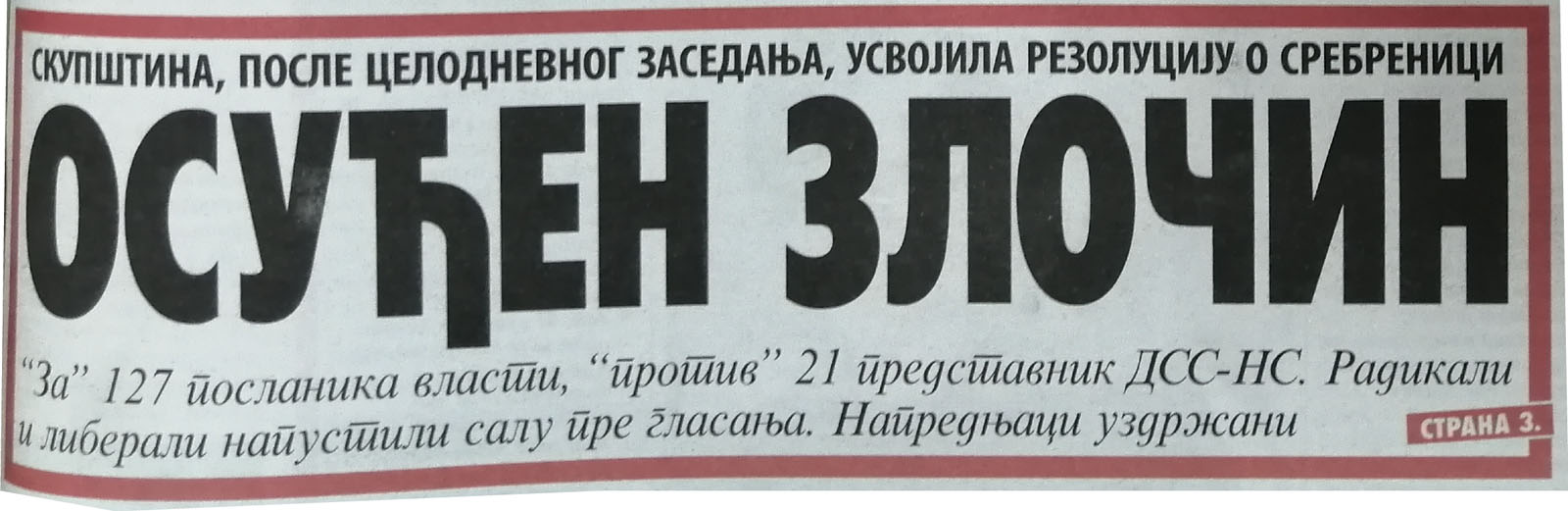

A debate was held in 2010 at the initiative of Boris Tadić, on a resolution by which the National Assembly of Serbia would condemn the crime in Srebrenica. After consultations with the parliamentary parties behind closed doors, the coalition “For a European Serbia” (headed by Tadić’s DS) proposed the text of the declaration on March 27, 2010. The text reads that the National Assembly of Serbia condemns the crime committed in Srebrenica “in the manner determined by the verdict of the International Court of Justice”, but the word “genocide” is not mentioned, although the ICJ verdict qualified the Srebrenica crime as genocide. Thus, this Declaration condemned and denied the genocide in Srebrenica at the same time. In addition to not containing the word “genocide”, the Declaration also avoided mentioning the number of victims, or explicitly naming the perpetrators. This text was undoubtedly the fruit of a political compromise, a consequence of the DS’s desire for the Declaration to be adopted at all costs, and in that way to demonstrate Serbia’s commitment to transitional justice and reconciliation to the international community.[6]

Exactly 127 out of a total of 250 Members of Parliament of the Assembly of Serbia voted for the proposed text of the Declaration on Srebrenica, and that is how this document was adopted. The declaration was supported by MPs of the coalition “For a European Serbia”, and the coalition gathered around the SPS. The DSS and New Serbia were against, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) abstained, and the MPs of the SRS and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) did not vote. During an all-day parliamentary debate broadcast by the public media service RTS, opponents of the Declaration (except the LDP) sought to challenge court-established facts regarding the Srebrenica genocide (number of victims, manner of killing, etc.), insisted on a simultaneous condemnation of crimes against Serbs, and warned that the Declaration was directed against Republika Srpska and the Serbian people. The LDP did not vote for the Declaration for the opposite reason – because the text did not contain the word “genocide”. Representatives of the ruling coalition, as the proponents of the text, tried to point out that crimes were always individual, and that Serbia would never forget “its own victims”.

The declaration was not followed by a broader public debate on Srebrenica and did not achieve any significant results in changing the attitude of Serbian society towards this crime. Different forms of institutional and non-institutional denial have remained present in the public discourse to the same extent as before the Declaration.

On 26 May 2011, Ratko Mladić, former Commander of the VRS Main Staff, indicted at the time before the ICTY for genocide in Srebrenica, was arrested. Just like Radovan Karadžić, Mladić was also arrested in Serbia, and the reactions to this arrest did not differ significantly from the reactions to Karadžić’s arrest: government officials did not elaborate on the crimes Mladić was accused of, while the opposition protested. As usual, President Tadić viewed the arrest as part of Serbia’s European integrations. “We have shown that we want to be part of Europe and that we want to raise our credibility with the international community”, Tadić said. His coalition partner and then-Minister of Internal Affairs Ivica Dačić spoke exclusively about the operational aspects of the arrest as a police action. The arrest of Mladić was harshly condemned by the SRS, at that time a parliamentary opposition party, which dubbed Mladić a “Serbian hero”, and his arrest “one of the strongest blows to Serbian national interests and the state of Serbia.”

2012-2021.

In 2012, the SNS came to power. The SNS was formed after the break-up of the SRS in 2008; so in the first period it was a parliamentary opposition party, and in the 2012 elections, it obtained the majority of votes and formed the government together with the SPS. The head of the government at the time was Ivica Dačić, and in the same year, the then president of the SNS, Tomislav Nikolić, won the elections for the President of Serbia. After the early parliamentary elections in 2014, the new SNS leader, Aleksandar Vučić, became the head of the Serbian government. First as Prime Minister, and since 2017, as President of Serbia, he gained enormous political power and, together with his party, took over all levels of state power in Serbia.

After the separation from the ultra-right SRS, the SNS tried to declaratively separate itself from the warmongering past and to present itself as a pro-European center-right party. The party managed to convince the international community of this – to a certain extent, at least. Reports by domestic and international NGOs and the media on systemic corruption in Serbia, the connection of the authorities with organised crime, the suppression of media freedom, and the abuse of public goods, have so far failed to threaten the SNS rule.

When it comes to the relation towards the past, the SNS has remained a nationalist party that enforces ethnocentric memory politics. In the commemorative practices of the state, there is room only for Serb victims, while other victims are ignored or denied. Attempts to establish the guilt of individuals and accept the responsibility of state institutions for war crimes are always presented as attempts to impose collective guilt on the Serbian people and as attacks on Serbia. Many war crimes indictees, as well as convicts who have served their sentences, enjoy favourable social reputations and appear regularly in the media and the public, where state resources have enabled them to promote their interpretation of the past.

In this period, when it comes to Srebrenica, the dominant issue that remains is the interpretative denial – a denial primarily of the legal qualification of the crimes; but their relativisation is also common – through comparisons with other crimes. However, a new type of literal denial is emerging that implies a denial that the verdicts of genocide exist at all: what is written in the verdicts is not disputed, but those same verdicts are denied as fact. For example, in 2012, the then President Nikolić stated that “there was no genocide” in Srebrenica, and that “genocide is difficult to prove in court” – which implies that the Srebrenica genocide was never proven in court. In March 2017, Aleksandar Vučić said that, “No one questions the gravity of the crimes in Srebrenica”, but that a new question arises: “What is it that makes someone want a legal qualification?” – which again suggests that the legal qualification, otherwise contained in the verdicts, (still) does not exist. In April 2021, on a national frequency TV station, the then Minister of Defense Aleksandar Vulin also denied the existence of verdicts which qualified the crime in Srebrenica as genocide. “Where was the genocide in Srebrenica proven, what court verdict states it, how was it done, who was convicted of genocide and not of a crime?” he wondered rhetorically, suggesting that such a verdict does not exist.

This narrative strategy seeks to create the belief that the genocide in Srebrenica is an arbitrary assessment, and not a legal qualification obtained through exhaustive evidentiary proceedings by courts whose jurisdiction the Republic of Serbia recognises.

Tomislav Nikolić, acting as President of Serbia in 2013, gave an interview to Bosnia and Herzegovina’s BHT TV Station, where he reiterated that no genocide had taken place in Srebrenica and that the genocide was “difficult to prove”. On behalf of Serbia, he apologised for “the crime committed in Srebrenica.” However, this apology did not carry weight, as it was both a denial of genocide and also its relativisation – because Nikolić also said on this occasion that “everything that happened during the war in the former Yugoslavia had elements of genocide.”

On the twentieth anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, in the summer of 2015, the United Kingdom submitted a motion for a resolution on Srebrenica to the United Nations Security Council. After the drafting of several versions of the text of the resolution, which treated the crime in Srebrenica as genocide, the UN Security Council rejected this proposal, because Russia vetoed it. The President of Serbia, Tomislav Nikolić, on that occasion stated that “Russia’s veto in the UN Security Council prevented it from tarnishing the entire Serbian people, and Moscow has shown that they are a true and sincere friend.” Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić also expressed satisfaction that the resolution draft was not adopted: “We believe that the goal of this resolution was not to contribute to reconciliation. We made the decision that, if the conditions were met, I would represent Serbia in Srebrenica on 11 July […].”

The conditions were met, and on 11 July 2015, Aleksandar Vučić went to the annual commemoration of the victims of Srebrenica in Potočari. At the commemoration, Vučić was first booed and then attacked with stones and bottles which were thrown at the procession in which he was. The pro-regime media in Serbia presented this as “attempted murder”, “assassination of Vučić” and “revenge on Serbs”. From that moment on until today, the anniversary of the genocide in Srebrenica in the public discourse of Serbia has taken place in the shadow of the anniversary of the incident in Potočari – which represents is a special kind of humiliation of the genocide victims, and a clear indication of official Serbia’s attitude towards that crime.

Between 2016 and 2021, first-instance and final judgments were reached against Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić, both of whom were found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica. However, the denial of the legal qualification of this crime had continued in Serbia, and, to date, no representative of the executive branch of government has acknowledged the genocide in Srebrenica.

Aleksandar Vučić has stopped publicly praising Ratko Mladić in the last ten years, unlike what he was doing while he was the SRS Secretary-General. Regarding the verdicts against Karadžić and Mladić, he has mostly been reticent and vague, emphasising the need to leave the past and look to the future, and not commenting on some of the verdicts. Just before the final verdict pronouncement against Ratko Mladić, on 8 June 2021, Vučić stated that “the Serbian people are facing a difficult situation”, and thus continued to identify the people with convicted war criminals. When in June and July 2021 the parliaments of Montenegro and Kosovo adopted resolutions defining the Srebrenica massacre as genocide, the President of Serbia dubbed this “the political abuse of Serbs.” To this day, Vučić has remained consistent in denying the genocide in Srebrenica and its relativisation through comparison with other crimes, as well as in holding to the line that Serbs and Serbia are threatened by the recognition of the genocide.

The same views on Srebrenica have been shared by the Prime Minister of Serbia, Ana Brnabić, from 2017 until today: denial of the genocide while recognising the crime, emphasis on the need to look to the future, and subscription to the inevitable relativisation by citing crimes against Serbs.

Other state officials who have been part of the government in the last 10 years do not have identical views on Srebrenica, but one thing they all have in common is the denial of the genocide and the insistence that this legal qualification is directed against Serbia, Republika Srpska, and the Serbs, as well as that Serbian casualties from previous wars were greater and more significant. While some politicians admit that a crime took place in Srebrenica (which must not be called genocide), others even deny the crime itself – mainly through the glorification of Ratko Mladić. Right-wing opposition parties also participate in the denial, both of the crimes and of the genocide.

There are very few political parties in Serbia whose official stand is that genocide was committed in Srebrenica in July 1995. These few include: the LDP, League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina, and Party of Democratic Action of Sandžak. These parties are marginal and have no significant influence on public opinion. Through collaboration with the ruling parties, they implicitly support the official memory politics regarding Srebrenica. In addition to these parties, the genocide in Srebrenica is also recognised by the initiative “Do not let Belgrade Drown”, the Movement of Free Citizens, and the Party of the Radical Left.

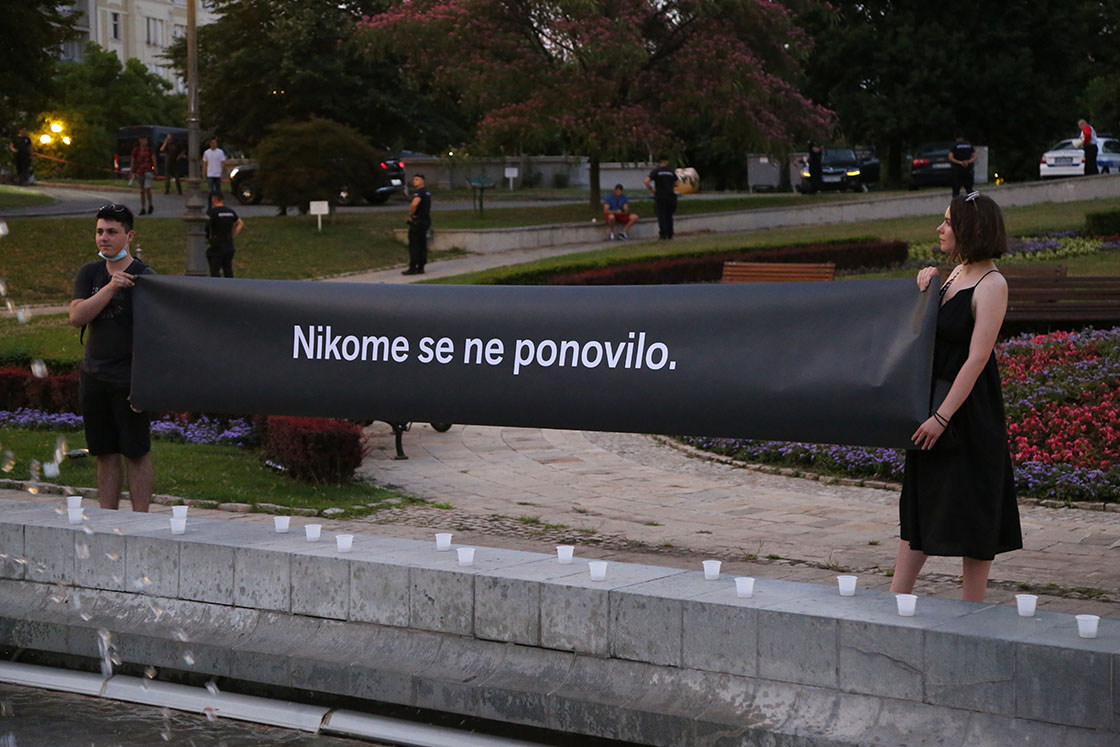

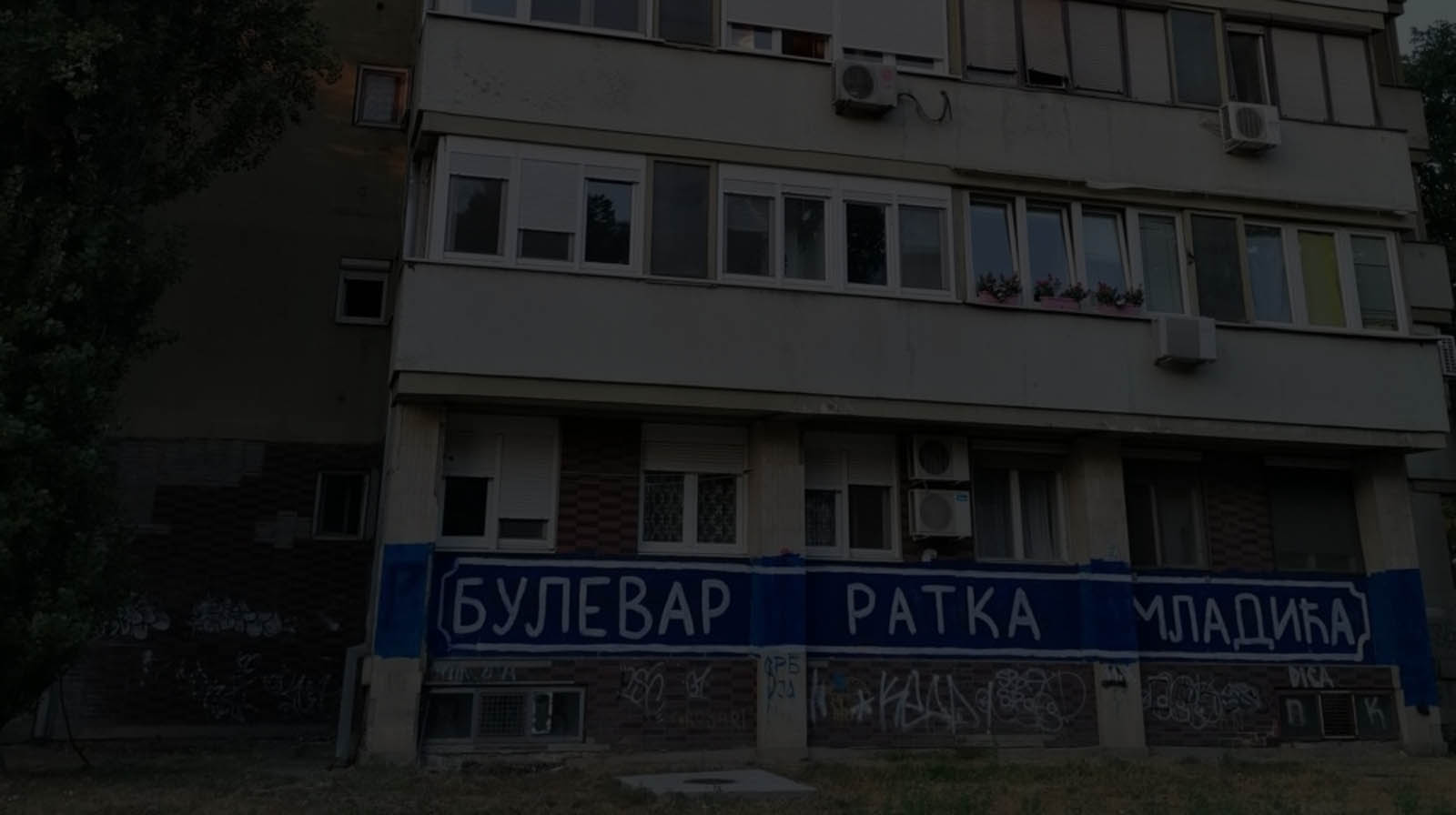

Only a part of the civil society in Serbia commemorates the anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide in an organised manner, among them the HLC. Women in Black organise a commemorative performance in Belgrade downtown every year, and the Youth Initiative for Human Rights has been lighting candles for the victims of Srebrenica every year since 2015. These street memorial actions are almost always targetted by right-wing groups, which come to the scene and try to obstruct the commemorations by chanting the praises of Ratko Mladić, belittling the victims of the genocide, and verbally attacking the participants. No government official has explicitly condemned the attacks.

On November 3, 2021, the Youth Initiative for Human Rights announced plans for the removal of the mural to Ratko Mladić, which has existed on a wall in the centre of Belgrade since July 2021. However, the Ministry of the Interior banned the gathering which goal was to erase the mural. And so the mural in honour of Ratko Mladić has become a memorial under state protection.

None of the government representatives participate in paying tribute to the victims of Srebrenica. To date, there are no official commemorations in Serbia.