Crimes against Croats in Vojvodina

„And I know it was good, we lived well in Hrtkovci. And now? Only, I decided: as long as I don’t go […] To leave that field, that fertile land; never. I will not move”

Intimidation campaign

In the period between 1991 and 1995, a campaign of intimidation and pressure on the Croatian population was being conducted on the territory of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina in the Republic of Serbia, with the aim of moving them out of their homes and getting them to leave Serbia. The campaign, varying in intensity and peaking in the second half of 1991, resulted in the expulsion, from the spring to autumn of 1992 and in the summer of 1995, of tens of thousands of Croats from Vojvodina.

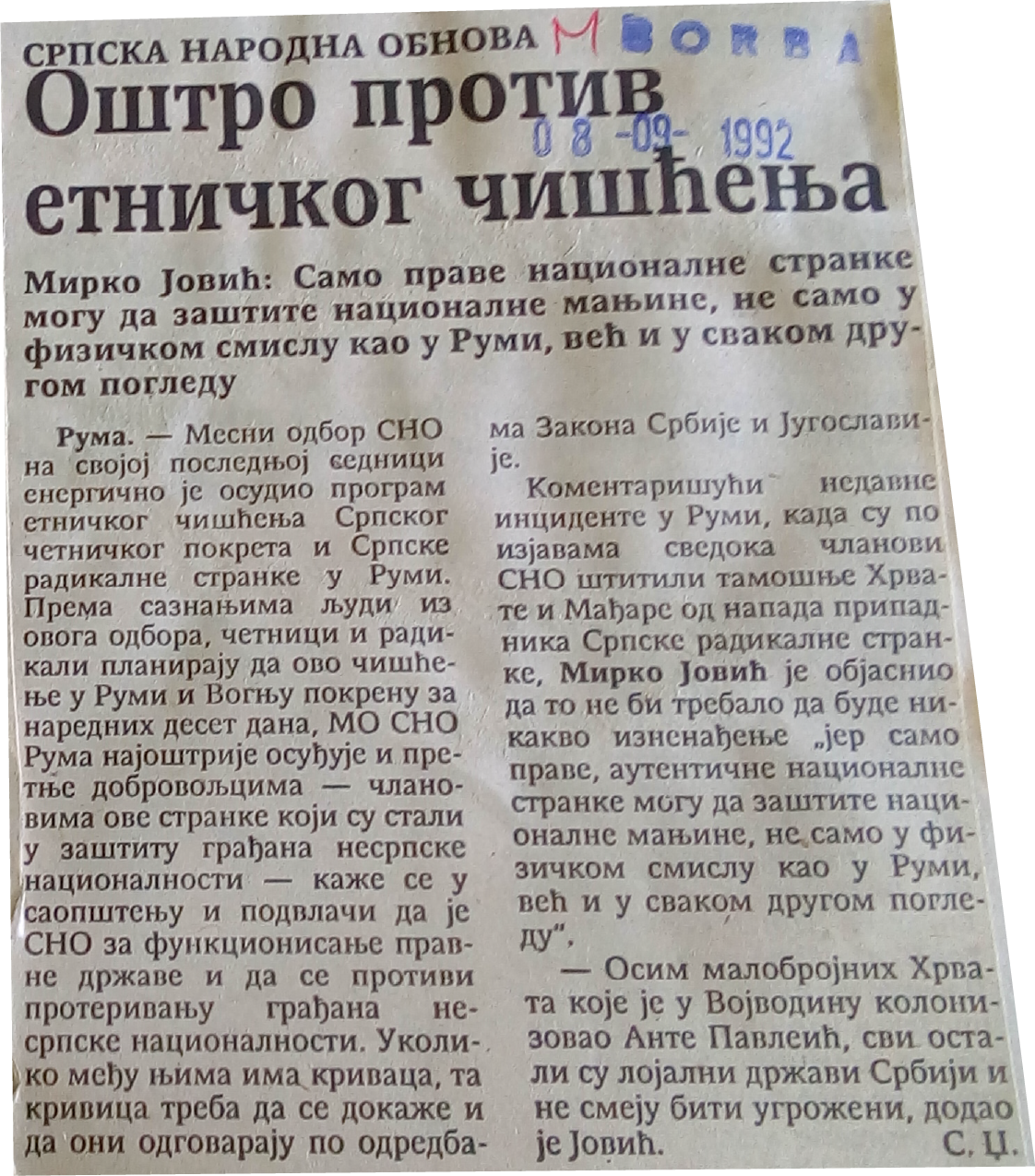

The main advocates and inspirers of the campaign of intimidation and pressure on the Croatian population in Vojvodina were Vojislav Šešelj and his Serbian Radical Party (SRS). The eviction of Croatian families was carried out under pressure from various groups close to the SRS, composed of the local population and the militant part of Serbian refugees from Croatia, as well as members of volunteer units from Serbia who took part in the wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH).

The campaign of intimidation took place with the knowledge and tacit approval of the political structures of the Republic of Serbia. In addition, members of the Ministry of the Interior (MUP) of the Republic of Serbia, as well as members of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) Reserve, took part in certain acts of violence against Croats. The Department of State Security (RDB) of the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Serbia also played a significant role in the forced eviction of Croats from Vojvodina.

Violence against the Croatian population of Vojvodina

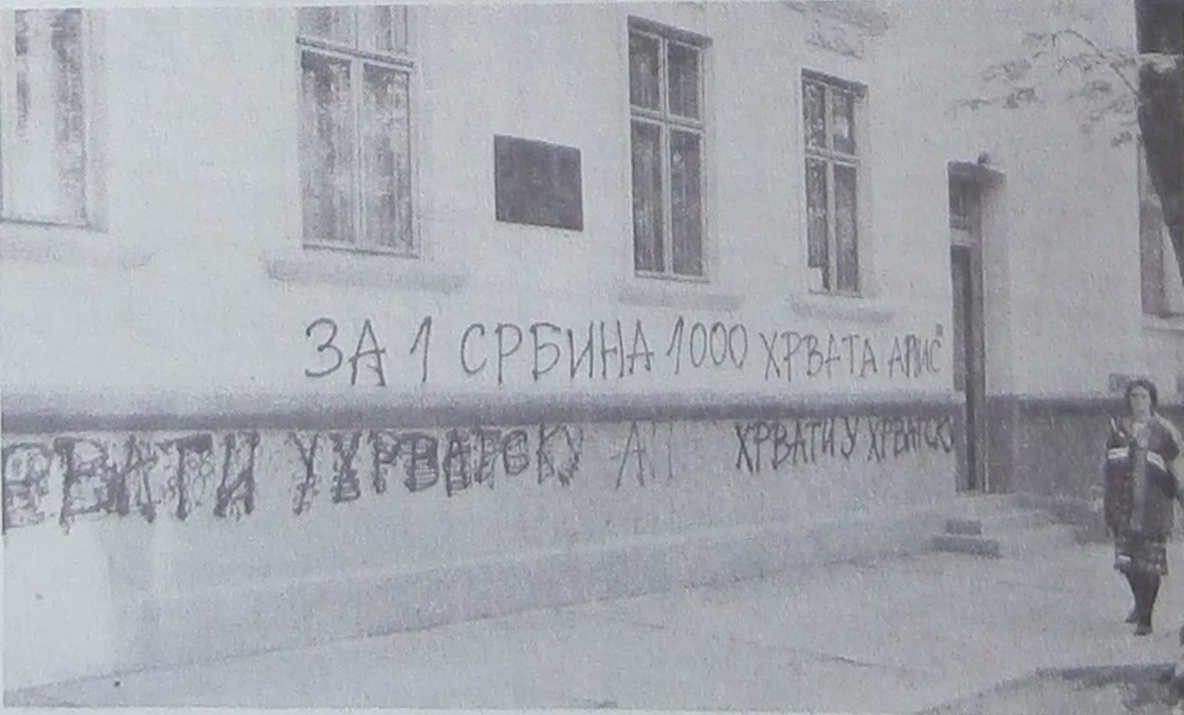

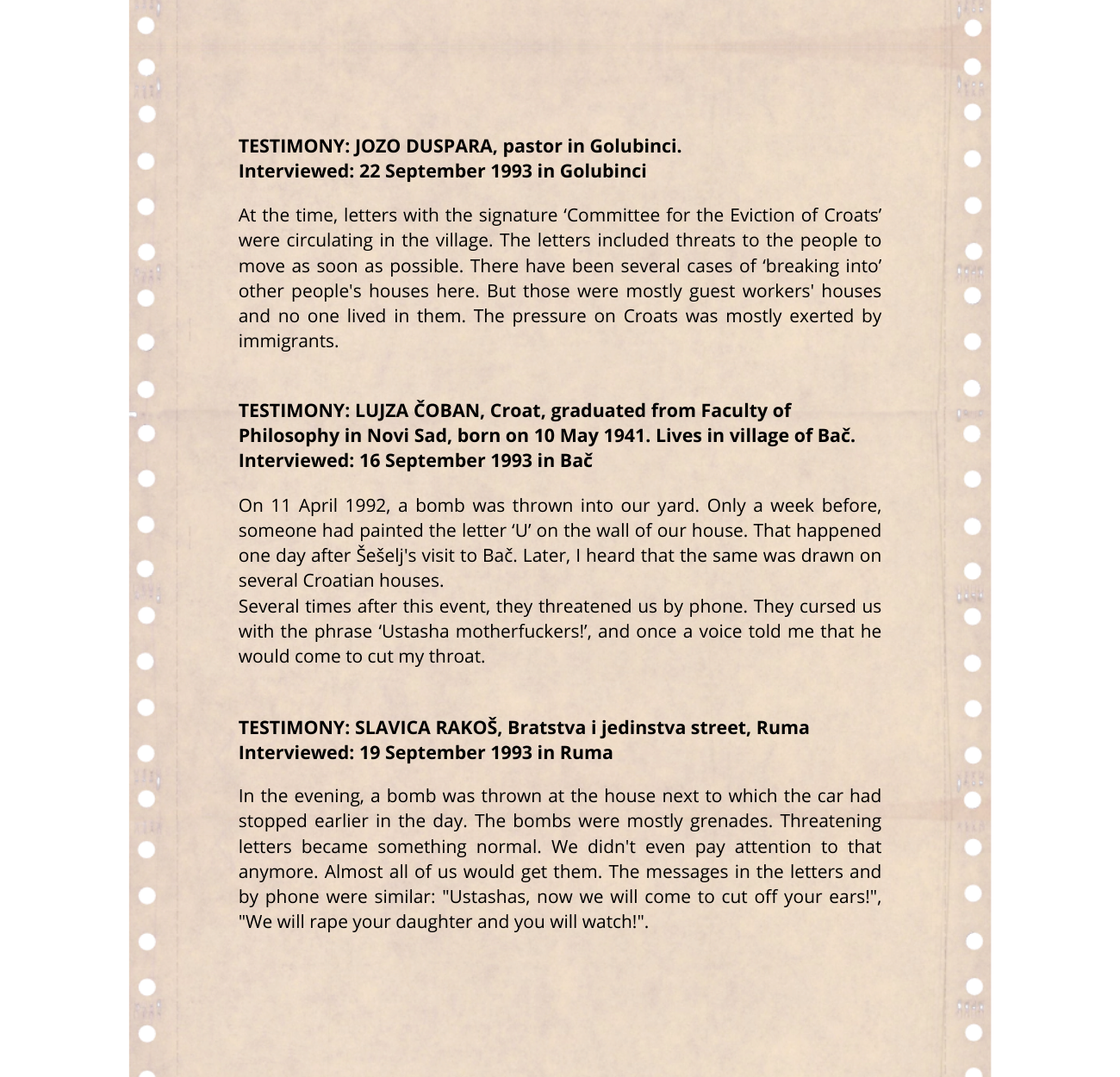

The expulsion of Croats and other non-Serbs throughout Vojvodina was carried out according to the same or a similar pattern. First, in the settlements inhabited by the Croatian population, persons unknown to the locals would appear and visit the houses of local Croats, asking the owners about the possibility of exchanging property. This was followed by telephone threats, the publication and sending of threatening leaflets and letters, writing of threatening graffiti, public name-calling of individuals and intrusions into houses, and subsequently, planting of explosives and dropping of bombs.

In addition to the above, there were cases of physical violence against the Croats of Vojvodina, as well as cases of murder. At public rallies, most often organized by the SRS, they would issue threats against Croats, as well as give ultimatums for moving out.

1991

In Vojvodina, ethnically motivated incidents started to occur sporadically from the autumn of 1990. The first recorded incident was the planting of explosives in the Franciscan monastery in Bač, in the autumn of 1990. After that, the monastery was damaged on two more occasions.

The campaign of intimidation and pressure on Vojvodina Croats was intensified after the events in Novi Slankamen in early May 1991. Namely, the conflict arose over the traditional display of flags on the occasion of 1 May at the building of the Croatian Peasant House. Putting the new Croatian flag with a checkerboard next to the Yugoslav flag, although until then it had been regular practice, was now interpreted as a provocation. During the night the flag was removed, and the whole event served as an excuse to threaten the local Croatian population.

In the following months, Croats in Novi Slankamen were exposed to threats and intimidation by from Stara Pazova (later a member of the Serbian Volunteer Guard) and the group gathered around him. The local Croatian population was threatened by telephone, bombs were thrown into their yards, and shots were fired at their houses and bars.

From the autumn of 1991, Croats in Ruma started to receive frequent telephone threats. Unidentified persons were telling them that they had two or three days to move out of their houses, or otherwise they would be killed.

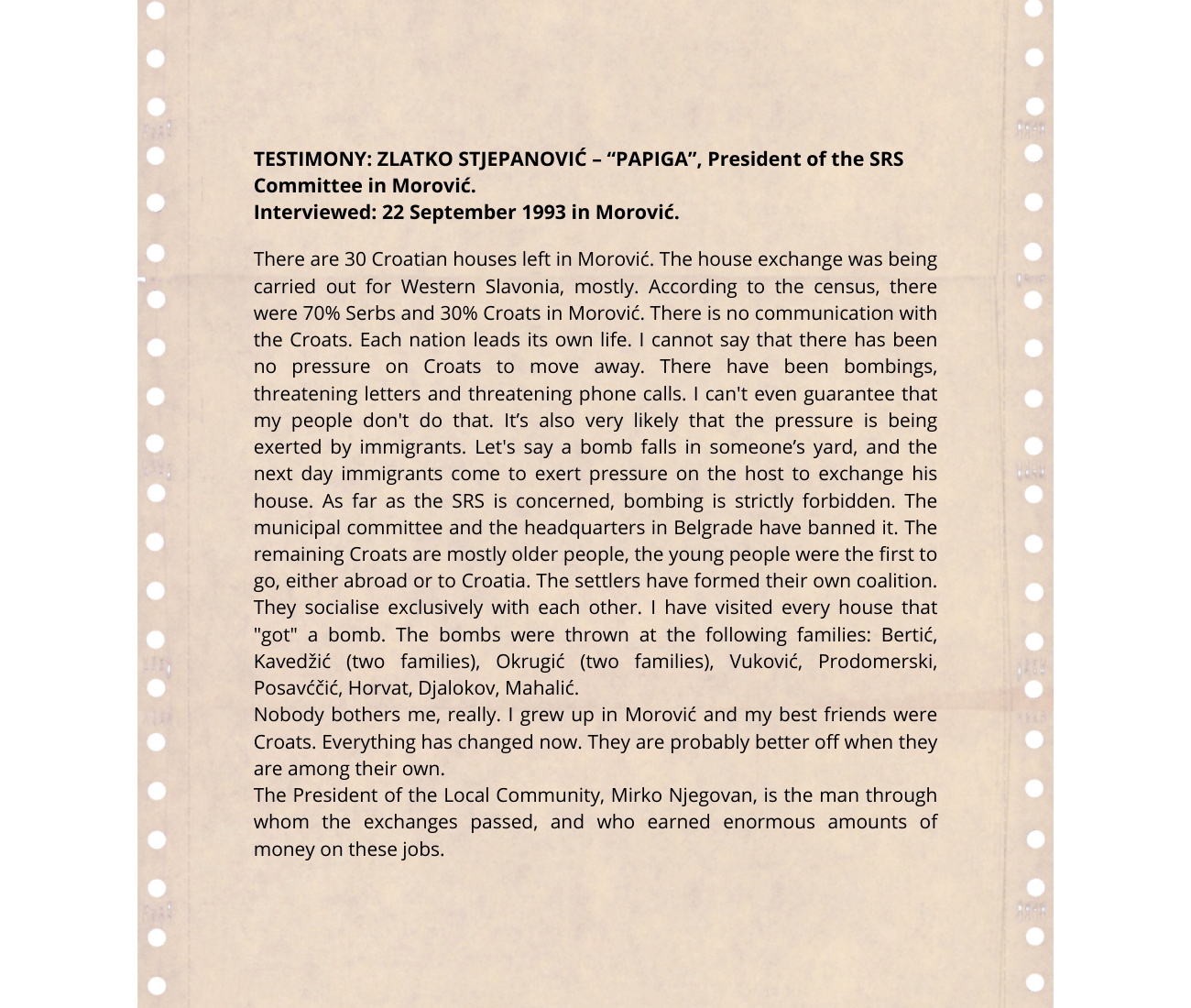

On the territory of the municipality of Šid, the targets were, at first, the more respectable, richer and more educated Croatian families. As the organisers of the threats and intimidations, the residents of villages around Šid identified members of the SRS, local Serbs – in the first place, Petar Živković, a former teacher and official of the SRS from the village of Sot, and Zlatko Stjepanović aka “Papiga” [Parrot], President of the SRS Committee of Morović.

In May 1991, a special unit of the Serbian Ministry of the Interior was stationed not far from the village of Kukujevci in the municipality of Šid. This unit was in charge of securing the border with Croatia, and had about a hundred members. Members of this special unit, led by , would enter Kukujevci every day with a transporter, search the houses of local Croats and take them out of their houses. They would take them outside the village, to a silo and hangar near the train station, where they mistreated and beat them. Croats from Kukujevci were often taken for questioning to the police station in Šid.

From September 1991 to August 1992, the JNA established several camps for Croats on the territory of Serbia: in Stajićevo near Zrenjanin, in the JNA barracks in Zrenjanin, in Begejci near Žitište, in the Penitentiary in Sremska Mitrovica, in the military prison in Šid, in the Penitentiary and Military Prison in Niš, Aleksinac, as well as in the Military Remand Prison in Belgrade and the underground facilities of the Institute for Security in Banjica (Belgrade).

Croatian civilians and soldiers from the area of Vukovar, Osijek and Vinkovci were being brought to these camps. The total number of prisoners in these camps was about 7,000. Prisoners in these camps were subjected to torture, starvation and humiliation. They were being forced to sleep on the floor, and food was scarce and of poor quality. The guards would attack the prisoners with batons and gunstocks, and with their arms and legs. There was a small, still unknown number of Croats from Vojvodina among the detainees in these camps.

1992

During 1992, the violence against the Croat population in Vojvodina intensified. From May 1992, in a number of ethnically mixed settlements in Vojvodina, organised pressure has been exerted on Croats by threats, throwing of bombs, planting of explosives, and breaking into and taking over their homes.

In the period from May to August 1992, the largest wave of emigration of Croats from the villages of Vojvodina was recorded, mostly from Hrtkovci, Kukujevci, Novi Slankamen, Beška and Petrovaradin. During that period, under pressure and threats, more than 10,000 Croats exchanged their property for the property of Serbs from Croatia.

6 May 1992, Hrtkovci

On 6 May 1992, the SRS held a pre-election rally in Hrtkovci in front of more than a thousand people, mostly Serbian refugees from Slavonia. Vojislav Šešelj gave a speech at that gathering, in which, among other things, he said:

„In this village, Hrtkovci, in this place of Serbian Srem, there is no place for Croats either. Which are the only Croats who belong among us? Only those Croats and their families who bled on the fronts together with us.”

„To every refugee Serbian family, we need to give the address of one Croatian family. The police will give it, the police will act as the government decides, and soon we will be the government. In a nice manner, all Serbian refugee families will come to the doors of Croats and give them their addresses in Zagreb and other Croatian places. They will, they will. There will be enough buses, we will take them to the border of Serbia, and from there let them continue on foot, if they don’t go alone.”

„I am convinced that you, Serbs from Hrtkovci and other villages in the vicinity, will also know how to preserve mutual harmony and unity, that you will very quickly get rid of the remaining Croats in your village and surroundings.”

Šešelj’s speech was accompanied by shouts of “Ustashas out!” and “Croats to Croatia!”.

The SRS rally was followed by organised violence against local Croats. The local Croatian population in Hrtkovci was exposed to intimidation, telephone threats, menacing leaflets and public calls for moving out. Offensive graffiti were being written and windows broken on the houses of Croats.

A number of Serbian refugees from Croatia, along with local Serbs close to the SRS, took part in the attacks aimed at intimidating Croats and other non-Serbs in Hrtkovci. They woul in groups, in an organised manner and ask the owners to hand over their houses, threatening to destroy their property and wielding weapons. Refugees would come to the houses with lists including addresses of Croats in Hrtkovci. They would tell homeowners that their houses were intended for exchange.

The Croatian population in Hrtkovci was also exposed to the planting of explosives and throwing of bombs into yards. In some cases, the bomb throwing was preceded by a visit from people inquiring about the exchange of houses, which was a kind of pressure for the population to agree to the exchange of property.

In the period from May 10, 1992 to July 1, 1992, about 20 Croatian families were physically evicted from their homes in Hrtkovci, while a large number of them succumbed to the pressure and agreed to . In the period from May to August 1992, about 450 Croatian and ethnically mixed families emigrated from Hrtkovci under pressure.

Ostoja Sibinčić, a clerk in the Municipality of Ruma and, since June 1992, President of the Hrtkovci Local Community, and Rade Čakmak, a refugee from Croatia, former Commander of the Territorial Defence (TO) of Grubišno Polje, were identified as the organisers of the pressure and violence against Croats in Hrtkovci.

The local government, led by Sibinčić, made the decision to change the names of streets and public institutions in Hrtkovci. The names of Croatian historical figures were replaced by the names of famous Serbs.

At the end of July 1992, a decision was made to change the name of the village Hrtkovci, and at the beginning of August 1992, the signboard with the name of the village was removed and a new one with the name Srbislavci was installed. The police wasn’t prevent the installation of the signboard, but a day later, they removed the board with the name Srbislavci.

1993

In the first half of 1993, the extent of forced relocations decreased, but the threats and intimidation of the non-Serbian population in Vojvodina by militant groups, aimed at the exchange of houses, continued. The pressure continued through telephone threats, bombings and the public name-calling of “undesirables”.

on 30 July 1993, in the village of Kukujevci in the area of Šid, led to a new wave of emigration of Croats from the territory of Vojvodina.

1995

After Operation “Flash” by the Croatian Army and Police in early May 1995, and then Operation “Storm” in August 1995, a large number of Serbian refugees came to Serbia from Croatia, from the area of Western Slavonia and the territory of the so-called Republika Srpska Krajina. A lot of them came to Vojvodina, which again led to interethnic tensions.

During 1995, the Croatian population was again being forcibly evicted and expelled from their homes by a militant group of Serbian refugees from Croatia, who were mostly armed and in uniform, with the support of the local population close to the SRS. The citizens of Serbian nationality, who stood up for the protection of their neighbours, were also exposed to attacks. Although the police responded to most incidents more quickly and adequately than in previous years, between May and October 1995 another 5,000 Croatian citizens emigrated from Serbia.

Resistance

A group of Belgrade intellectuals, gathered in the Belgrade Circle and the Civil Resistance Movement, spoke with locals and refugees in Hrtkovci on several occasions during the spring of 1992. By mid-July 1992, they had organised seven press conferences in Hrtkovci, and one in Golubinci.

In addition, they would regularly inform the public about the events in Srem. In mid-July 1992, a delegation of Belgrade intellectuals submitted to Federal Minister of Justice Tibor Varadi the First report on violations of the rights of non-Serbian citizens to personal and property security, which provided information on the endangerment of non-Serb citizens in Hrtkovci, Golubinci and Ruma.

In mid-August 1992, a delegation of residents of Golubinci, Hrtkovci and Ruma informed Justice Minister Tibor Varadi and FRY Minister of Human Rights and Minority Rights Momčilo Grubač of the violence against the Croat population in Vojvodina and the lack of police response. This visit, along with the campaign and reports of civic groups and anti-war activists on endangering the personal and property security of Croats in Vojvodina, and the campaign of the independent media, led to a reaction from the authorities and the arrest of Ostoja Sibinčić, Rade Čakmak and several other Serbian refugees from Croatia in Hrtkovci.

Selection of Documents

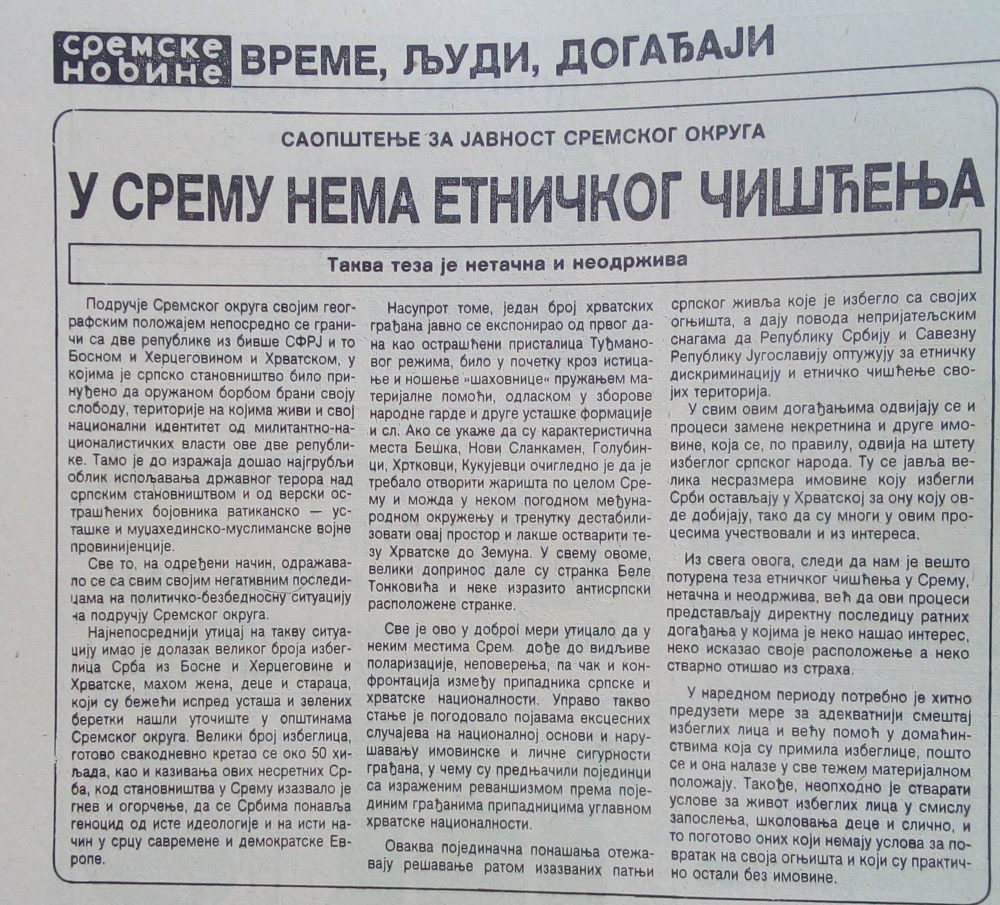

Government reaction to pressures and the emigration of the Croatian population

The arrest of Ostoja Sibinčić and others, in August 1992, was presented to the public as a guarantee of respect for the human rights of non-Serbian citizens, although it was clear that the government’s reaction

was delayed, i.e., after a large number of Croats had already left Vojvodina. However, following the reaction of the federal authorities, the provincial and republican authorities did not even then deal with the responsibility of the main political ideologists and inspirers of the persecution of Croats from Vojvodina, but reduced everything to individual incidents, stating that “those who want to move away are moving away and everything will be done to prevent any moving out under pressure”.

Sibinčić and Čakmak spent three months in custody, after which they were released pending trial. During their detention, interethnic tensions and incidents in Hrtkovci were reduced.

However, after the court’s decision to release the suspects pending trial, a group of Serbian refugees gathered again around Ostoja Sibinčić and Rade Čakmak, and again began to put pressure on Croats and ethnically mixed families, and also on those Serbs who demanded equal rights for all residents of Hrtkovci regardless of their nationality.

In May 1993, Ostoja Sibinčić was found guilty of endangering security, while he and Čakmak were convicted of illegal possession of weapons. Despite the fact that he was sentenced to a suspended prison sentence, Ostoja Sibinčić remained head of the Assembly of MZ (Local Community) Hrtkovci after the end of the trial against him.

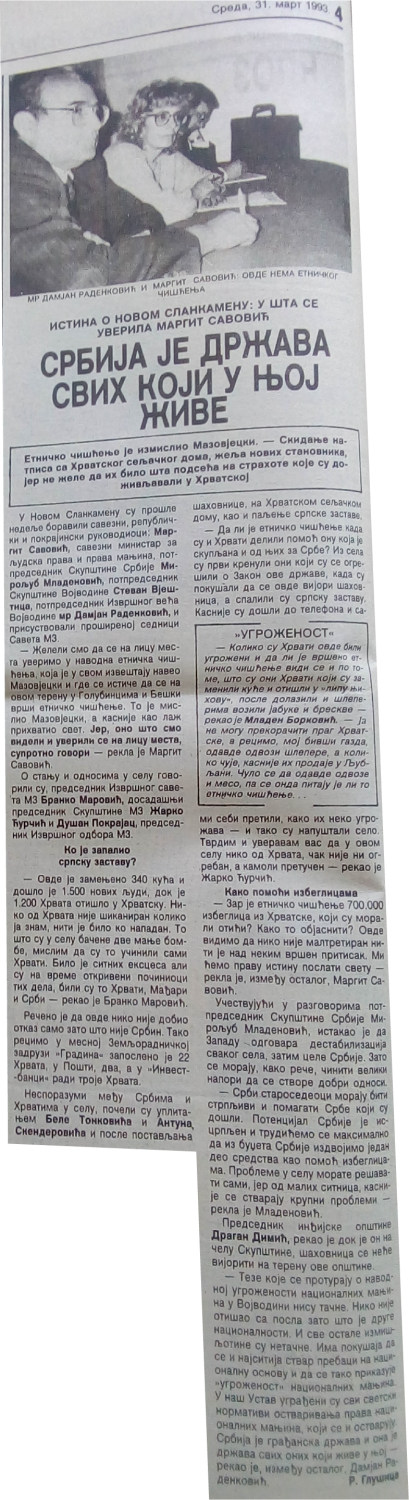

At the beginning of 1993, faced with public pressure and , representatives of all levels of government in Serbia would deny or reduce both the pressures and the problem of the emigration of the Croatian population from Vojvodina. In their response, they rejected allegations of pressure on the non-Serbian population of Vojvodina and the endangerment of local Croats, shifting the responsibility to the so-called “external factor”, and concluding that “the destabilisation of every village, and consequently the whole of Serbia, is convenient for the West”.

In July 1993, the Federal Ministry for Human Rights and Minority Rights, now headed by Margit Savović, took the position that “[in] FR Yugoslavia, the Republic of Serbia and the province of Vojvodina, something like that has never happened, nor will happen.” However, the destruction of property, the forcible occupation of houses, the planting of explosives and the killing of Croats had been widespread in Vojvodina. By July 1993, at least ten Croats from Vojvodina had been killed or disappeared, and more than 10,000 Croats had been evicted.

Despite the denial of the eviction of Croats under pressure by the authorities, in October 1993 several persons, members and sympathisers of the SRS and members of the Serbian Chetnik Movement were arrested on the territory of Srem on suspicion of committing crimes against civilians, inciting and participating in ethnically motivated violence, about which the Department of State Security of the MUP Serbia had information.

Selection of Documents

Murders and disappearances of Croats in Vojvodina

During the campaign of intimidation and pressure on Vojvodina’s Croats in the period from 1991 to 1995, a number of ethnically motivated murders were committed. These murders additionally contributed to the creation of an atmosphere of fear and the emigration of Croats from the territory of Vojvodina.

Although during the investigation the Humanitarian Law Centre obtained information that many more murders of Croats had been committed, the following cases were definitely confirmed from several sources:

1991 – murder of Krešimir Herceg (b. 1938) from Višnjićevo

1992 – murder of Živan Marušić (b 1939) from Jamena, murder following the abduction of Franjo (b. 1975), Ana (b. 1932) and Jozo (b. 1931) Matijević from Kukujevaci, murder of Mijat Štefanac (b. 1951) from Hrtkovaci, murder of Nada and Stevan Guštin from Bač

1993 – murder of Stevan Krošlak (b. 1940) from Sot, murder of Marija Tomić (b. 1906), Agica (b. 1943) and Nikola (b. 1940) Oskomić from Kukujevaci

1994 – murder of Marija Purić (b. 1966) from Golubinci

1995 – murder of Živko Litrić (b.1936) from Kukujevaci

Stevan Đurkov from Sonta and brothers Mato and Ivica Abjanović from Morović are still on the lists of missing persons.

Stevan Đurkov (b. 1956), a Croat from Sonta, was arrested on 27 September 1991 in Sonta, and was reportedly last seen the same day in the village of Dalj in Croatia.

On 27 September 1991, the “Ronta” café, owned by Stevan Đurkov in Sonta, was surrounded by a dozen unidentified armed persons in camouflage uniforms with white belts. They took Đurkov out of the café and drove him in a van in an unknown direction.

Shortly afterwards, Stevan Đurkov’s family received information that Stevan was seen at the entrance to the police station in Dalj, on the territory controlled by the Serbian armed forces of the so-called SAO Slavonia, Baranja and Western Srem.

Stevan Đurkov’s wife reported his disappearance to the Red Cross in Apatin, and after three or four days, went to the TO headquarters in Dalj to inquire about Stevan. There, she learned from a member of the Serbian TO, Milorad Stričević, that Stevan was at the TO headquarters, and that he was being held “because Stevan is a Croatian spy”.

Milorad Stričević aka “Stalin” from Dalj was a member of the so-called “space police” or security unit within the Dalj TO. This unit was in charge of detaining and interrogating the non-Serbian population in Dalj. Stričević was directly subordinate to Željko Ražnatović Arkan, the commander of the Serbian Volunteer Guard.

During the conversation, Milorad Stričević told Stevan Đurkov’s wife to come the next day and then she would be able to see her husband.

A day later, Stevan Đurkov’s wife went back to the TO headquarters in Dalj, but did not find Stričević there. The people who were there pretended they didn’t know who Stričević was.

According to of 15 October 1991, Milorad Stričević passed to the JNA security authorities inaccurate information that some citizens of Sonta were preparing the assassination of a JNA colonel, and because of this, members of the JNA military police came to Sonta and arrested several citizens.

At the trial of Goran Hadžić before the ICTY

that a man from Sonta was reported to Stričević for displaying the Croatian flag at his café.

Stevan Đurkov is still in the records of missing persons of the International Committee of the Red Cross

Brothers Mato (b. 1950) and Ivica (b. 1952) Abjanović were taken from their house on 23 October 1991, and that was the last time they were seen alive.

On 23 October 1991, four uniformed and armed men came to the Abjanović family’s house in the village of Morović, municipality of Šid. They came in two grey cars with JNA registration plates. In the house at that moment were Mato Abjanović, his mother Marija, his wife Gordana, and their children, minors.

Uniformed persons surrounded the house, and then went inside and asked Mato Abjanović to come to the police station in Šid for questioning. Although they claimed to have an order for questioning, they did not show it to the Abjanović family. Mato Abjanović offered no resistance. At that moment, Mato’s brother, Ivica Abjanović, came to the house from the neighbouring yard.

When it became clear that the uniformed persons would not abandon their intention to take Mato for questioning, Ivica Abjanović decided to go with them. That was the last time the brothers were seen by anyone.

The same evening, 23 October 1991, Mato’s wife and son went to the Šid police station to ask what had happened. She spoke with the then chief of police in Šid, Nedeljko Makivić, who told her that he had not issued an official warrant for the apprehension or arrest of the Abjanović brothers.

The next morning, Gordana Abjanović went to the SUP building in Šid again, this time with Marija Abjanović, mother of Mato and Ivica. Police Chief Makivić then told them that the Abjanović brothers had been taken away by “the other side”. When asked by Marija Abjanović which party that was and what it was all about, the mayor said: “They were removed by the Ustashas”, which implied that the Croatian side was responsible for their fate.

The Abjanović family have never received official information about what happened to Mato and Ivica.

The RDB of Serbia had information about the ethnically motivated murders and forced abductions of Vojvodina’s Croats.

Case of the Barbalić family in Zemun

On July 1, 1997, Ljiljana Mihajlović (then Mijoković), Vojislav Šešelj’s secretary, moved by force into a municipal apartment in Zemun where the Barbalić family had tenancy rights, with the help of other SRS members. The Barbalić family was on vacation at the time of the breaking into the apartment.

The Barbalić family returned to Zemun on 3 July 1997, but could no longer enter the apartment. On the same day, Ljiljana Mihajlović signed a lease contract with the municipality of Zemun, whose president at the time was Vojislav Šešelj. Over the following days, Mihajlović signed a contract for the purchase of the apartment with the municipality.

The Barbalić family reported a case of burglary to the police in Zemun, demanding that the unidentified people who had moved in the apartment be evicted. The police told the Barbalić family that they were “not unidentified people, because they had shown their ID cards when asked to.”

The Barbalić family sought protection in court, and in July 1997, the Fourth Municipal Court in Belgrade issued a temporary measure ordering the Barbalić family to return to the apartment from which they had been forcibly evicted.

However, the police, with the public support of the representatives of the authorities of the municipality of Zemun, in which the SRS had a majority, refused to assist in the execution of the temporary measure of eviction of the illegal occupants.

Owing to the forcible eviction of the Barbalić family from their apartment in July 1997, several protests were held by the citizens of Zemun and Belgrade, demanding compliance with the court’s decision to return the apartment to the Barbalić family. Despite the protests, this did not happen.

During the protest against the eviction of the Barbalić family, citizens of Zemun of non-Serbian nationality were exposed to threatening phone calls, with unidentified persons telling them that they were on the eviction list, and that they should be careful how they acted if they didn’t want something to happen to them.

The SRS used to publish personal details of the Barbalić family, including the details of family member who was a minor, in the municipal newspaper „Zemunske novine“, as well as in the party newspaper „Velika Srbija“, calling them “Ustashas” and “fake Zemun citizens”. The editor of “Zemunske novine” at the time was Ognjen Mihajlović, the husband of Ljiljana Mihajlović.

After many years of struggle in the courts to get the apartment back, in t mid-2019 the Constitutional Court of Serbia accepted the Barbalić family’s appeal, but only in the part related to the trial being within a reasonable time, while the appeal related to the violated rights to an explanatory court decision and legal certainty and to property rights was rejected. The case is currently before the European Court of Human Rights.

Consequences

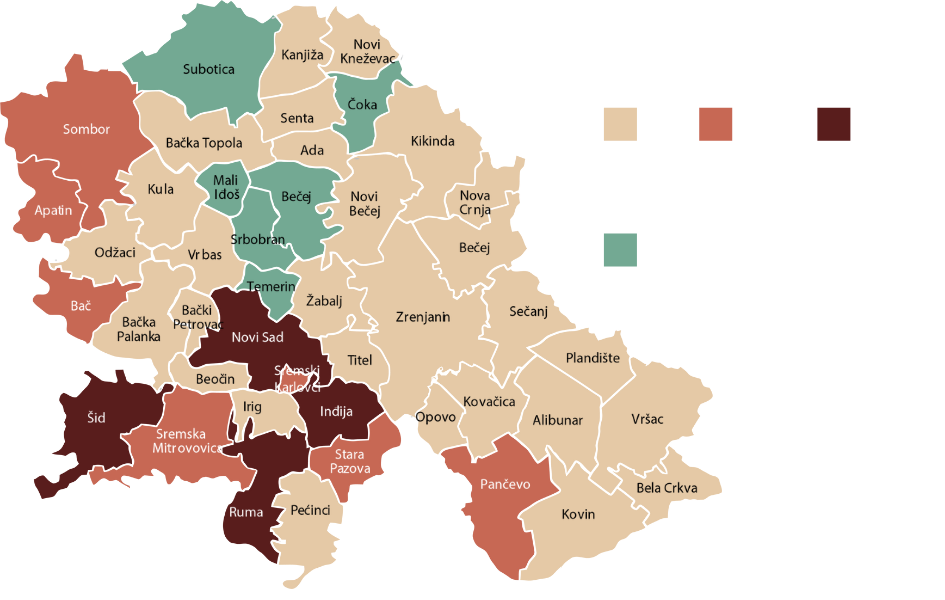

In the period between two censuses, in 1991 and 2002, a decrease in the number of Croats and other non-Serbs on the territory of Vojvodina was noticeable. The number of Croats decreased in 39 out of 45 municipalities in Vojvodina, and on the territory of the whole of Vojvodina, the number of Croats decreased by 18,262, or 24.41%. in the Croatian population in Vojvodina is largely due to the policy of persecution of the Croatian population in the period from 1991 to 1995.

At the municipal level, the largest decrease in the share of the Croatian population in the total population was noted in Šid, and it was 65.5%. At the settlement level, the largest decrease was noted in the village of Kukujevci, municipality of Šid, where, according to the 1991 census, 1,622 Croats used to live, accounting for 89% of the total population of the village. By 2002, the number of Croats in Kukujevci had dropped to 72, or 3.2% of the total population of the village.

Verdict on Vojislav Šešelj

In April 2018, the Appeals Chamber of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) partially revoked the acquittal of Vojislav Šešelj by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and found him guilty of inciting persecution (forcible displacement), deportation and other inhumane acts (forcible transfer) as a crime against humanity, and also of persecution (violation of the right to security) as a crime against humanity in Hrtkovci in Vojvodina. The Appeals Chamber sentenced Vojislav Šešelj to 10 years in prison.

The verdict on Vojislav Šešelj is at the same time the only verdict issued before international and domestic courts for the forced eviction of Croats from Vojvodina, i.e., from Hrtkovci.

The verdict established that immediately after Vojislav Šešelj’s speech on 6 May 1992 in Hrtkovci, a large number of Croats were forced to leave the village. According to the Appeals Chamber, this speech encouraged violence against the Croatian population of Hrtkovci, which resulted in their departure. It was further stated that Croats were pressured to exchange their properties for the properties of Serbs from Croatia – they were exposed to harassment and intimidation. It was also established that the local authorities did nothing to protect the Croatian population and prevent their eviction.

Culture of remembrance

On 27 February 2004, the Assembly of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina adopted 43 Declaration on the invitation for the return of all citizens who were forced to leave Vojvodina between 1990 and 2000. With this Declaration, the Assembly of AP Vojvodina invited all the citizens “who had been forced to leave Vojvodina in the period 1990-2000”, owing to political, economic, ethnic reasons, to return to Vojvodina. “The invitation, however, did not lead to the return of Croats to Vojvodina, nor to the development of remembrance of the events that had led to their departure.

The pressure and violence to which the Croats of Vojvodina were exposed during the 1990s are no longer a topic among the public in Serbia. The ruling politicians rarely talk about it, media reports are almost non-existent, and no crimes against Croats on the territory of Vojvodina have been memorialised. Instead, in mid-2018, Vojislav Šešelj bought a house in Hrtkovci, where the congresses of the Serbian Radical Party have been held ever since.